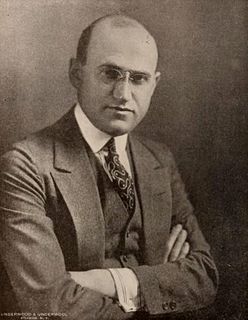

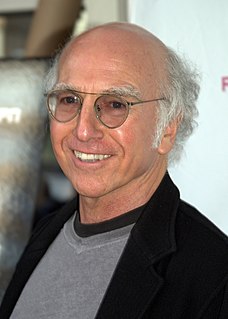

A Quote by Aaron Sorkin

I consider plot a necessary intrusion on what I really want to do, which is write snappy dialogue.

Related Quotes

When I'm writing a script, before I can write dialogue or anything, I have two or three hundred pages of notes, which takes me a year. So, it's not like "what happens next." I've got things that I'm thinking about but I don't settle on them. And if I try to write dialogue before then, I can't. It's just garbage.

What must novel dialogue . . . really be and do? It must be pointed, intentional, relevant. It must crystallize situation. It must express character. It must advance plot. During dialogue, the characters confront one another. The confrontation is in itself an occasion. Each one of these occasions, throughout the novel, is unique.

The way you write dialogue is the same whether you're writing for movies or TV or games. We use movie scriptwriting software to write the screenplays for our games, but naturally we have things in the script that you would never have in a movie script -- different branches and optional dialogue, for example. But still, when it comes to storytelling and dialogue, they are very much the same.