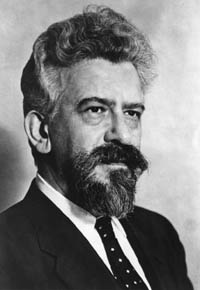

A Quote by Abraham Joshua Heschel

Our concern is not how to worship in the catacombs but how to remain human in the skyscrapers.

Related Quotes

Christians, indeed, have a special obligation not to forget how great and how inextinguishable the human proclivity for violence is, or how many victims it has claimed, for they worship a God who does not merely take the part of those victims, but who was himself one of them, murdered by the combined authority and moral prudence of the political, religious, and legal powers of human society.

How do we define, how do we describe, how do we explain and/or understand ourselves? What sort of creatures do we take ourselves to be? What are we? Who are we? Why are we? How do we come to be what or who we are or take ourselves to be? How do we give an account of ourselves? How do we account for ourselves, our actions, interactions, transactions (praxis), our biologic processes? Our specific human existence?

I think that every educator, indeed every human being, is concerned with what is true and what is not; what experiences to cherish and which ones to avoid; and how best to relate to other human beings. We differ in how conscious we are of these questions; how reflective we are about our own stances; whether we are aware of how these human virtues are threatened by critiques (philosophical, cultural) and by technologies (chiefly the digital media). A good educator should help us all to navigate our way in this tangled web of virtues.

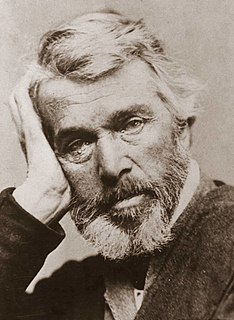

Theologians and philosophers, who make God the creator of Nature and the architect of the Universe, reveal Him to us as an illogical and unbalanced Being. They declare He is benevolent because they are afraid of Him, but they are forced to admit the truth that His ways are vicious and beyond understanding. They attribute a malignity to Him seldom to be found in any human being. And that is how they get human beings to worship Him. For our miserable species would never lavish worship on a just and benevolent God from whom they had nothing to fear.

Art deals with profound and simple moods. Let us suppose that the artist - in this instance (the artist) Picabia - gets a certain impression by looking at our skyscrapers, our city, our way of life, and that he tries to reproduce it. He will convey it in plastic ways on the canvas, even though we see neither skyscrapers nor city on it.