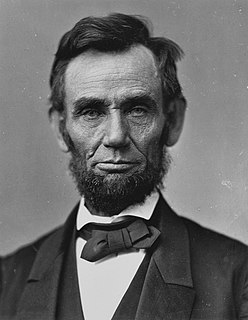

A Quote by Abraham Lincoln

Next came the Patent laws. These began in England in 1624; and, in this country, with the adoption of our constitution. Before then [these?], any man might instantly use what another had invented; so that the inventor had no special advantage from his own invention. The patent system changed this; secured to the inventor, for a limited time, the exclusive use of his invention; and thereby added the fuel of interest to the fire of genius, in the discovery and production of new and useful things.

Quote Topics

Added

Adoption

Advantage

Another

Any

Before

Began

Came

Changed

Constitution

Country

Discovery

England

Exclusive

Fire

Fuel

Genius

Had

His

Instantly

Interest

Invented

Invention

Inventor

Laws

Limited

Limited Time

Man

Might

New

Next

Our

Own

Patent

Patent Law

Production

Secured

Special

System

Then

Thereby

Things

Time

Use

Useful

Useful Things

Related Quotes

I have called this phenomenon of stealing common knowledge and indigenous science "biopiracy" and "intellectual piracy." According to patent systems we shouldn't be able to patent what exists as "prior art." But the United States patent system is somewhat perverted. First of all, it does not treat the prior art of other societies as "prior art." Therefore anyone from the United States can travel to another country, find out about the use of a medicinal plant, or find a seed that farmers use, come back here, claim it as an invention or an innovation.

In the world's history certain inventions and discoveries occurred, of peculiar value, on account of their great efficiency in facilitating all other inventions and discoveries. Of these were the art of writing and of printing - the discovery of America, and the introduction of Patent-laws. The date of the first ... is unknown; but it certainly was as much as fifteen hundred years before the Christian era; the second-printing-came in 1436, or nearly three thousand years after the first. The others followed more rapidly - the discovery of America in 1492, and the first patent laws in 1624.

In England, an inventor is regarded almost as a crazy man, and in too many instances invention ends in disappointment and poverty. In America, an inventor is honoured, help is forthcoming, and the exercise of ingenuity, the application of science to the work of man, is there the shortest road to wealth.

In England, an inventor is regarded almost as a crazy man, and in too many instances, invention ends in disappointment and poverty. In America, an inventor is honoured, help is forthcoming, and the exercise of ingenuity, the application of science to the work of man, is there the shortest road to wealth.

Somehow I felt that if Fox Talbot had had more time and more drawing talent, he would have filled in the interval between his two drawings and made a complete panorama. Now, 163 years later, I was able to use his great invention to elaborate on his youthful dream of capturing and fixing the fleeting image. In doing so, I may also have added another little bit to the soul of this extraordinary place.

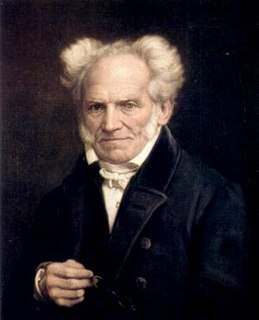

Genius is its own reward; for the best that one is, one must necessarily be for oneself. . . . Further, genius consists in the working of the free intellect., and as a consequence the productions of genius serve no useful purpose. The work of genius may be music, philosophy, painting, or poetry; it is nothing for use or profit. To be useless and unprofitable is one of the characteristics of genius; it is their patent of nobility.

There are many points in the history of an invention which the inventor himself is apt to overlook as trifling, but in which posterity never fail to take a deep interest. The progress of the human mind is never traced with such a lively interest as through the steps by which it perfects a great invention; and there is certainly no invention respecting which this minute information will be more eagerly sought after, than in the case of the steam-engine.

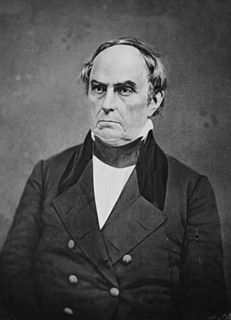

That reminds me to remark, in passing, that the very first official thing I did, in my administration-and it was on the first day of it, too-was to start a patent office; for I knew that a country without a patent office and good patent laws was just a crab, and couldn't travel any way but sideways or backways.

It may be that the invention of the aeroplane flying-machine will be deemed to have been of less material value to the world than the discovery of Bessemer and open-hearth steel, or the perfection of the telegraph, or the introduction of new and more scientific methods in the management of our great industrial works. To us, however, the conquest of the air, to use a hackneyed phrase, is a technical triumph so dramatic and so amazing that it overshadows in importance every feat that the inventor has accomplished.