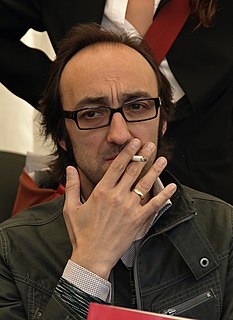

A Quote by Agustin Fernandez Mallo

For me, every translation is a new book, with the translator inevitably broadening the meaning of the original book in any translation.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

Translation is a kind of transubstantiation; one poem becomes another. You can choose your philosophy of translation just as you choose how to live: the free adaptation that sacrifices detail to meaning, the strict crib that sacrifices meaning to exactitude. The poet moves from life to language, the translator moves from language to life; both, like the immigrant, try to identify the invisible, what's between the lines, the mysterious implications.

There is an old Italian proverb about the nature of translation: "Traddutore, traditore!" This means simply, "Translators-traitors!" Of course, as you can see, something is lost in the translation of this pithy expression: there is great similarity in both the spelling and the pronunciation of the original saying, but these get diluted once they are put in English dress. Even the translation of this proverb illustrates its truth!

In translation studies we talk about domestication - translation styles that make something familiar - or estrangement - translation styles that make something radically different. I use a lot of both in my translation, and modernism does both. For instance, if you look at the way James Joyce presents Ulysses, is that domesticating a classic? Think of it as an experiment in relation to a well-known text in another language.

I've never translated more than one book by any author. But I'm fascinated by translators who have, like Richard Zenith, who's translated so much of Fernando Pessoa's work. I get restless for a new kind of influence. The books I've translated are books I want to learn from as a writer, to be intoxicated by. And translation is an act of writing in itself. It's an act of recreation - of a writer's cadence and tone and everything that distinguishes the voice in the book.