A Quote by Al Gore

Well-established theories collapse under the weight of new facts and observations which cannot be explained, and then accumulate to the point where the once useful theory is clearly obsolete.

Related Quotes

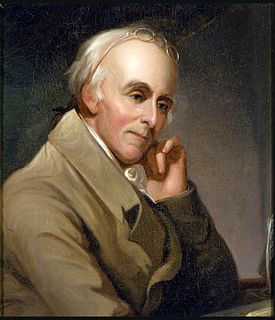

Were I disposed to consider the comparative merit of each of them [facts or theories in medical practice], I should derive most of the evils of medicine from supposed facts, and ascribe all the remedies which have been uniformly and extensively useful, to such theories as are true. Facts are combined and rendered useful only by means of theories, and the more disposed men are to reason, the more minute and extensive they become in their observations

Difficulties arise when reported observations seem to conflict with 'facts' that the majority of scientists accept as established and immutable. Scientists tend to reject conflicting observations.....Nevertheless, the history of science shows that new observations and theories can eventually prevail.

Facts and theories are different things, not rungs in a hierarchy of increasing certainty. Facts are the world's data. Theories are structures of ideas that explain and interpret facts. Facts do not go away while scientists debate rival theories for explaining them. Einstein's theory of gravitation replaced Newton's, but apples did not suspend themselves in mid-air pending the outcome.

Progress is achieved by exchanging our theories for new ones which go further than the old, until we find one based on a larger number of facts. ... Theories are only hypotheses, verified by more or less numerous facts. Those verified by the most facts are the best, but even then they are never final, never to be absolutely believed.

Scientific theories need reconstruction every now and then. If they didn't need reconstruction they would be facts, not theories. The more facts we know, the less radical become the changes in our theories. Hence they are becoming more and more constant. But take the theory of gravitation; it has not been changed in four hundred years.

No theory ever agrees with all the facts in its domain, yet it is not always the theory that is to blame. Facts are constituted by older ideologies, and a clash between facts and theories may be proof of progress. It is also a first step in our attempt to find the principles implicit in familiar observational notions.

The more experiences and experiments accumulate in the exploration of nature, the more precarious the theories become. But it is not always good to discard them immediately on this account. For every hypothesis which once was sound was useful for thinking of previous phenomena in the proper interrelations and for keeping them in context. We ought to set down contradictory experiences separately, until enough have accumulated to make building a new structure worthwhile.

In these researches I followed the principles of the experimental method that we have established, i.e., that, in presence of a well-noted, new fact which contradicts a theory, instead of keeping the theory and abandoning the fact, I should keep and study the fact, and I hastened to give up the theory.

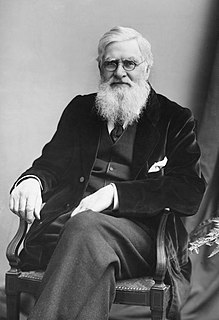

To be sure, Darwin's theory of evolution is imperfect. However, the fact that a scientific theory cannot yet render an explanation on every point should not be used as a pretext to thrust an untestable alternative hypothesis grounded in religion into the science classroom or to misrepresent well-established scientific propositions.

In less than eight years "The Origin of Species" has produced conviction in the minds of a majority of the most eminent living men of science. New facts, new problems, new difficulties as they arise are accepted, solved, or removed by this theory; and its principles are illustrated by the progress and conclusions of every well established branch of human knowledge.

First, it is necessary to study the facts, to multiply the number of observations, and then later to search for formulas that connect them so as thus to discern the particular laws governing a certain class of phenomena. In general, it is not until after these particular laws have been established that one can expect to discover and articulate the more general laws that complete theories by bringing a multitude of apparently very diverse phenomena together under a single governing principle.

For I am well aware that scarcely a single point is discussed in this volume on which facts cannot be adduced, often apparently leading to conclusions directly opposite to those at which I have arrived. A fair result can be obtained only by fully stating and balancing the facts and arguments on both sides of each question.