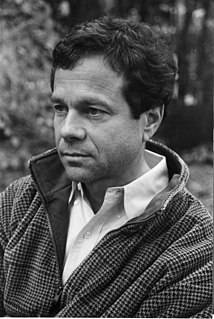

A Quote by Alan Lightman

The history of science can be viewed as the recasting of phenomena that were once thought to be accidents as phenomena that can be understood in terms of fundamental causes and principles.

Related Quotes

In the final, the positive, state, the mind has given over the vain search after absolute notions, the origin and destination of the universe, and the causes of phenomena, and applies itself to the study of their laws - that is, their invariable relations of succession and resemblance. Reasoning and observation, duly combined, are the means of this knowledge. What is now understood when we speak of an explanation of facts is simply the establishment of a connection between single phenomena and some general facts.

In real science a hypothesis can never be proved true...A science which confines itself to correlating phenomena can never learn anything about the reality underlying the phenomena, while a science which goes further than this and introduces hypotheses about reality, can never acquire certain knowledge of a positive kind about reality; in whatever way we proceed, this is forever denied us.

Science as we now understand the word is of later birth. If its germinal origin may be traced to the early period when Observation, Induction, and Deduction were first employed, its birth must be referred to that comparatively recent period when the mind, rejecting the primitive tendency to seek in supernatural agencies for an explanation of all external phenomena, endeavoured, by a systematic investigation of the phenomena themselves to discover their invariable order and connection.

There is a conceptual depth as well as a purely visual depth. The first is discovered by science; the second is revealed in art. The first aids us in understanding the reasons of things; the second in seeing their forms. In science we try to trace phenomena back to their first causes, and to general laws and principles. In art we are absorbed in their immediate appearance, and we enjoy this appearance to the fullest extent in all its richness and variety. Here we are not concerned with the uniformity of laws but with the multiformity and diversity of intuitions.

In the first stage of insight-building, all that researchers can do is observe phenomena. Second, they classify the phenomena in a way that helps them simplify the apparent complexities of the world so they can ignore the meaningless differences and draw connections between the things that really seem to matter. Third, based on the classification system, they propose a theory. The theory is a statement of what causes what and why, and under what circumstances.

Laplace considers astronomy a science of observation, because we can only observe the movements of the planets; we cannot reach them, indeed, to alter their course and to experiment with them. "On earth," said Laplace, "we make phenomena vary by experiments; in the sky, we carefully define all the phenomena presented to us by celestial motion." Certain physicians call medicine a science of observations, because they wrongly think that experimentation is inapplicable to it.