A Quote by Allen W. Wood

It was an important part of Mendelssohn's philosophical and religious view that the traditional rationalist proofs for God's existence should be sound an convincing. Kant thought they were not. So Kant's critique was world-shaking for Mendelssohn.

Related Quotes

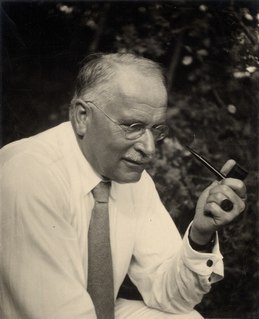

Just as we might take Darwin as an example of the normal extraverted thinking type, the normal introverted thinking type could be represented by Kant. The one speaks with facts, the other relies on the subjective factor. Darwin ranges over the wide field of objective reality, Kant restricts himself to a critique of knowledge.

There is a very common, though also very silly, picture of Kant according to which as empirical beings we are not free at all, and we are free only as noumenal jellyfish floating about in an intelligible sea above the heavens, outside any context in which our supposedly "free" choices could have any conceivable human meaning or significance. Part of the problem here is that Kant faces up honestly to the fact that how freedom is possible is a deep philosophical problem to which there is no solution we can rationally comprehend.

Kant, discussing the various modes of perception by which the human mind apprehends nature, concluded that it is specially prone to see nature through mathematical spectacles. Just as a man wearing blue spectacles would see only a blue world, so Kant thought that, with our mental bias, we tend to see only a mathematical world.

The everyday world, as Kant proved, is mere appearance. But it is also the only world in which we can make sense of the idea of a plurality of distinct individuals. We can only distinguish things as different if they occupy different regions of space-time. It follows (a point Kant missed but which the mystics have always understood) that reality 'in itself' is 'beyond plurality' and is, in that sense, 'One'.

Kant argued that, where nature could be considered beautiful in her acts of destruction, human violence appeared instead as monstrous. However, a misreading of Kant in Romantic philosophy led to the idealization of the murderer as a sublime genius that has colored constructions of that criminal figure ever since.