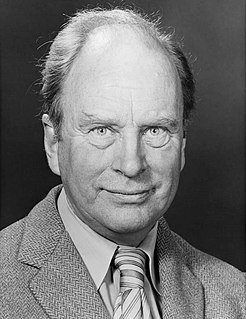

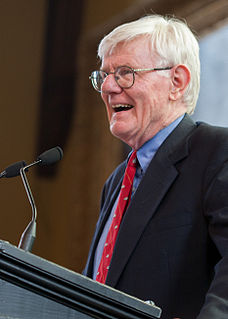

A Quote by Allen W. Wood

It is a culturally interesting (but also deeply depressing) fact that many religious claims seem to retain their emotional power for believers only if taken in ways that are intellectually unsupportable and even morally contemptible.

Related Quotes

Both Kant and Fichte thought of traditions of revealed religion as ways of symbolically (that is, with aesthetic emotional power) thinking about our moral condition. Both thought that religion would become more and not less powerful, emotionally and morally, if the claims of scriptures and religious teachings were taken symbolically rather than literally (whatever 'literally' might mean in the case of claims that are either nonsensical or outdated or historically unsupportable if taken as metaphysical or historical assertions).

The religious quality of Marxism also explains a characteristic attitude of the orthodox Marxist toward opponents. To him, as to any believer in a Faith, the opponent is not merely in error but in sin. Dissent is disapproved of not only intellectually but also morally. There cannot be any excuse for it once the Message has been revealed.

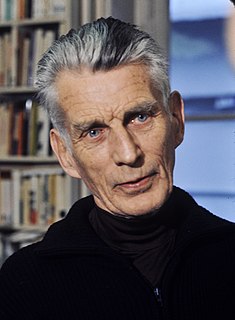

The fact would seem to be, if in my situation one may speak of facts, not only that I shall have to speak of things of which I cannot speak, but also, which is even more interesting, but also that I, which is if possible even more interesting, that I shall have to, I forget, no matter. And at the same time I am obliged to speak. I shall never be silent. Never.

Faithiest resonated with me in many ways-not only because, like Chris, I am a gay former-Christian atheist who still thinks of my religious neighbors as fellow truth-seekers-but also because I deeply appreciated the book's nuanced approach to contentious issues. This is an important contribution to current debates, one which should be read not only for its valuable content but also for its exemplary tone: warm, engaging, optimistic, and humble.

Believers often forget that most atheists used to be religious, that many non-believers used to think they had a personal relationship with their God and they used to 'feel' the power of prayer. They've since learned that it was all a farce, that their feelings were internal emotions and not some external force.

Of course, it's always difficult to disentangle fact from fiction in relation to, e.g., the singularity project. Many scientists I know are dismissive of transhumanist claims, BUT the last 100 years has surely taught us never to underestimate the pace and scope of scientific progress. However, even if much of this turns out to be science-fiction, it also reveals a way of thinking about human life that I find deeply troubling.

In the end, of course, all novelists will be judged by their novels, but let's not forget that we will also need new ways of assessing the latter. There are people who will continue to write nineteenth-century novels in the early twenty-first, and even win major prizes for them, but that's not very interesting, intellectually or emotionally.