A Quote by Allison Joseph

Each poem seems to demand its own formal approach. In both drafting and revision, I'll play around with line lengths and stanza formations, eventually letting the poem settle into what I think is its own best form.

Related Quotes

The subject of the poem usually dictates the rhythm or the rhyme and its form. Sometimes, when you finish the poem and you think the poem is finished, the poem says, "You're not finished with me yet," and you have to go back and revise, and you may have another poem altogether. It has its own life to live.

I want each poem to be ambiguous enough that its meaning can shift, depending on the reader's own frame of reference, and depending on the reader's mood. That's why negative capability matters; if the poet stops short of fully controlling each poem's meaning, the reader can make the poem his or her own.

It was early on in 1965 when I wrote some of my first poems. I sent a poem to 'Harper's' magazine because they paid a dollar a line. I had an eighteen-line poem, and just as I was putting it into the envelope, I stopped and decided to make it a thirty-six-line poem. It seemed like the poem came back the next day: no letter, nothing.

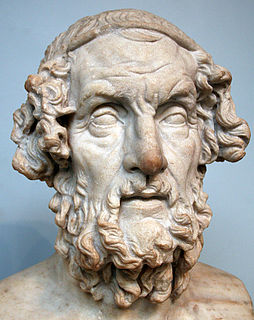

Poetry is perhaps the oldest art form. We can go back to an age-old idea of naming things, the Adamic impulse - to give something a name has always been an immensely powerful thing. To name something is to own it, to capture it. A poem is still a kind of spell, an incantation. Historically, a poem also invoked: it was a blessing, or a curse, or a charm. It had a motile power, was able to summon something into being. A poem is a special kind of speech-act. In a good poem there's the trance-like effect of language in its most concentrated, naked form.

I think what gets a poem going is an initiating line. Sometimes a first line will occur, and it goes nowhere; but other times - and this, I think, is a sense you develop - I can tell that the line wants to continue. If it does, I can feel a sense of momentum - the poem finds a reason for continuing.