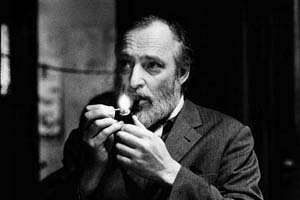

A Quote by Alton Tobey

My art career actually began under the kitchen table. My mother wanted to get me out of her hair while she cooked, so she laid out some paper and pencils on the floor under the kitchen table.

Related Quotes

When we were arguing on my twenty-fourth birthday, she left the kitchen, came back with a pistol, and fired it at me five times from right across the table. But she missed. It wasn't my life she was after. It was more. She wanted to eat my heart and be lost in the desert with what she'd done, she wanted to fall on her knees and give birth from it, she wanted to hurt me as only a child can be hurt by its mother.

A light was on in the kitchen. His mother sat at the kitchen table, as still as a statue. Her hands were clasped together, and she stared fixatedly at a small stain on the tablecloth. Gregor remembered seeing her that way so many nights after his dad had disappeared. He didn't know what to say. He didn't want to scare her or shock her or ever give her any more pain. So, he stepped into the light of the kitchen and said the one thing he knew she wanted to hear most in the world. "Hey, Mom. We're home.

Sometimes she goes out to work as a practical nurse, and comes home and sits by the kitchen table soaking her feet in a pan of hot water and Epsom salts. When she gets into bed and the springs creak under her weight, she groans with the pleasure of lying stretched out on an object that understands her so well.

He began to trace a pattern on the table with the nail of his thumb. "She kept saying she wanted to keep things exactly the way they were, and that she wished she could stop everything from changing. She got really nervous, like, talking about the future. She once told me that she could see herself now, and she could also see the kind of life she wanted to have - kids, husband, suburbs, you know - but she couldn't figure out how to get from point A to point B.

She reached up and lay her hand on my cheek. "You have the sweetest face," she said, looking at me dreamily. "It's like the perfect kitchen." I fought not to smile. This was the delirium. She'd fade in and out of it before the profound exhaustion dragged her down into unconsciousness. If you see someone spouting nonsense to themselves in an alleyway in Tarbean, odds are they're not actually crazy, just a sweet-eater deranged by too much denner. "A kitchen?" "Yes," she said. "Everything matches and the sugar bowl is right where it should be.

I was always a person on my mother's hip in the kitchen. My mom really wanted her kids at her side as much as possible, and she worked in restaurants for over fifty years. And my grandfather had ten children, and he grew and prepared most of the food. My grandmother, on my mother's side, was the family seamstress and the baker. So my mom, the eldest child, was always in the kitchen with my grandpa and I was always in the production and restaurant kitchens and our own kitchen with my mom. And it's just something that has always spoken to me.

She serves me a piece of it a few minutes out of the oven. A little steam rises from the slits on top. Sugar and spice - cinnamon - burned into the crust. But she's wearing these dark glasses in the kitchen at ten o'clock in the morning - everything nice - as she watches me break off a piece, bring it to my mouth, and blow on it. My daughter's kitchen, in winter. I fork the pie in and tell myself to stay out of it. She says she loves him. No way could it be worse.

I never asked my mother where babies came from but I remember clearly the day she volunteered the information....my mother called me to set the table for dinner. She sat me down in the kitchen, and under the classic caveat of 'loving each other very, very much,' explained that when a man and a woman hug tightly, the man plants a seed in the woman. The seed grows into a baby. Then she sent me to the pantry to get placemats. As a direct result of this conversation, I wouldn't hug my father for two months.

No, books. She would have maybe twenty going at a time, lying all over our house--on the kitchen table, by her bed, the bathroom, our car, her bags, a little stack at the edge of each stair. And she'd use anything she could find for a bookmark. My missing sock, an apple core, her reading glasses, another book, a fork.

How big are souls anyway?" asked Coraline. The other mother sat down at the kitchen table and leaned against the back wall, saying nothing. She picked at her teeth with a long crimson-varnished fingernail, then she tapped the finger, gently, tap-tap-tap against the polished black surface of her black button eyes.