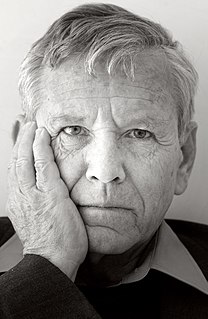

A Quote by Amos Oz

Writing in modern Hebrew is a bit like playing chamber music inside a huge, empty cathedral. If you are not very careful with the echoes, you may evoke some monstrosities.

Related Quotes

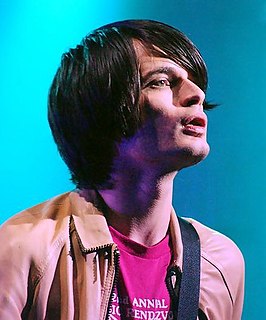

Music is the one art we all have inside. We may not be able to play an instrument, but we can sing along or clap or tap our feet. Have you ever seen a baby bouncing up and down in the crib in time to some music? When you think of it, some of that baby's first messages from his or her parents may have been lullabies, or at least the music of their speaking voices. All of us have had the experience of hearing a tune from childhood and having that melody evoke a memory or a feeling. The music we hear early on tends to stay with us all our lives.

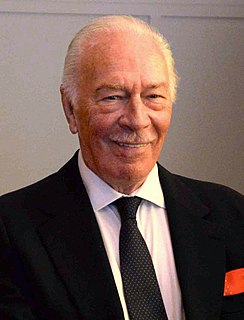

When you start, the world of publishing seems like a great cathedral citadel of talent, resisting attempts to let you inside. It isn't like that at all. It may be more difficult now, and take longer than when I started to write, but there's a great, empty warehouse out there looking for simple talent.

The revival of Hebrew, as a spoken language, is a fascinating story, which I'm afraid I cannot squeeze into a few sentences. But, let me give you a clue. Think about Elizabethan English, where the entire English language behaved pretty much like molten lava, like a volcano in mid-eruption. Modern Hebrew has some things in common with Elizabethan English. It is being reshaped and it's expanding very rapidly in various directions. This is not to say that every one of us Israeli writers is a William Shakespeare, but there is a certain similarity to Elizabethan English.

Music's always part of my writing. I think all art is interconnected. You can't create or experience one without its influences bleeding into another. In my writing, music's mostly something that feeds my inspiration and mood while I'm writing, but it's also taught me how to score scenes and even novels. The rise and fall of the storyline echoes the flow of a good piece of music.