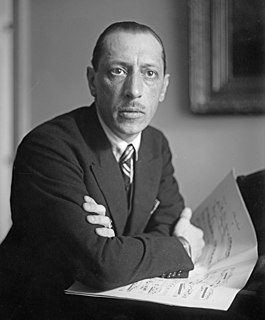

A Quote by Andre Kostelanetz

The conductor has the advantage of not seeing the audience.

Related Quotes

Normally classical music is set up so you have professionals on a stage and a bunch of audience - it's us versus them. You spend your entire time as an audience member looking at the back of the conductor so you're already aware of a certain kind of hierarchy when you are there: there are people who can do it, who are on stage, and you aren't on stage so you can't do it. There's also a conductor who is telling the people who are onstage exactly what to do and when to do it and so you know that person is more important than the people on stage.

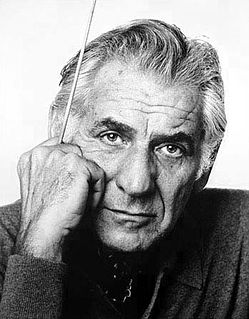

Perhaps the chief requirement of [the conductor] is that he be humble before the composer; that he never interpose himself between the music and the audience; that all his efforts, however strenuous or glamorous, be made in the service of the composer's meaning - the music itself, which, after all, is the whole reason for the conductor's existence.

I didn't have traditional stage fright. If there was 500 people in the audience or three people in the audience, it didn't really make a difference. What made a difference was the conductor. Everything that I was scared about as a drummer was him. It was his face. It was whether or not he'd approve of my playing.