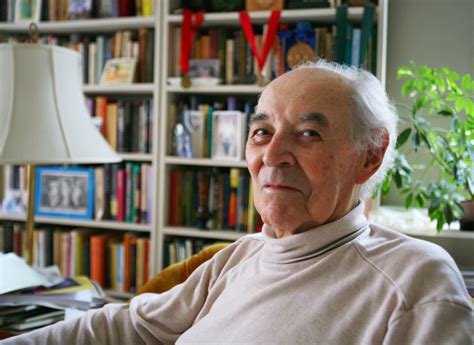

A Quote by Andreï Makine

The translator of prose is the slave of the author, and the translator of poetry is his rival.

Related Quotes

The translator has to be a good writer. The translator has to hear music too. And it might not be exactly your music because the translator needs to translate the music. And so, that is what you are hoping for: a translator who gets what you are doing but who also gets all the ways in which it won't work in the new language.

Poetry has an indirect way of hinting at things. Poetry is feminine. Prose is masculine. Prose, the very structure of it, is logical; poetry is basically illogical. Prose has to be clear-cut; poetry has to be vague - that's its beauty, its quality. Prose simply says what it says; poetry says many things. Prose is needed in the day-to-day world, in the marketplace. But whenever something of the heart has to be said, prose is always found inadequate - one has to fall back to poetry.

To me a translator is very, very important. If the fixer is also the translator, so much the better. I have known photographers who didn't speak the language and would work in a place for weeks without one, getting by on common sense and smiles. But how many situations did they miss because they couldn't talk to someone and get the back story on details, small daily life things, etc.

Poetry is the most direct and simple means of expressing oneself in words: the most primitive nations have poetry, but only quitewell developed civilizations can produce good prose. So don't think of poetry as a perverse and unnatural way of distorting ordinary prose statements: prose is a much less natural way of speaking than poetry is. If you listen to small children, and to the amount of chanting and singsong in their speech, you'll see what I mean.