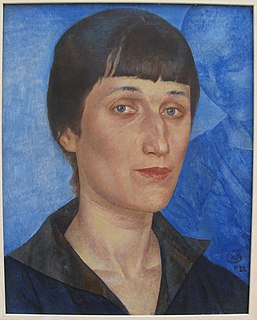

A Quote by Anna Akhmatova

In the terrible years of the Yezhov terror I spent seventeen months waiting in line outside the prison in Leningrad. One day somebody in the crowd identified me . . . and asked me in a whisper . . . "Can you describe this?" And I said: "I can."

Related Quotes

During the terrible years of the Yekhov terror I spent seventeen months in the prison queues in Leningrad. One day someone ‘identified’ me. Then a woman with lips blue with cold who was standing behind me, and of course had never heard of my name, came out of the numbness which affected us all and whispered in my ear—(we all spoke in whispers there): ‘Could you describe this?’ I said, ‘I can!’ Then something resembling a smile slipped over what had once been her face.

I went in for an audition [for As Good As It Gets], but the audition was with James L. Brooks. I was the first girl in that morning, and there was a whole waiting room of girls waiting to read for it. So I did my audition, and he asked me to step outside. So I stepped outside, and when he asked me to come back in, he looked at me, and he said, "Well, I'm very excited to work with you on set." And I was, like, "What?" I thought it was a Hollywood blow-off.

Nothing changed in my life since I work all the time," Pamuk said then. "I've spent 30 years writing fiction. For the first 10 years I worried about money and no one asked me how much money I made. The second decade I spent money and no one was asking me about that. And I've spent the last 10 years with everyone expecting to hear how I spend the money, which I will not do.

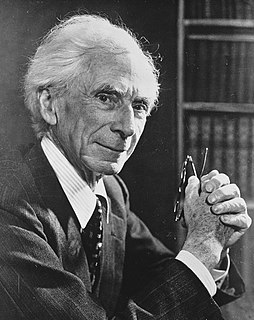

Prison is a severe and terrible punishment; but for me, thanks to Arthur Balfour, this was not so. I was much cheered on my arrival by the warder at the gate, who had to take particulars about me. He asked my religion, and I replied 'agnostic.' He asked how to spell it, and remarked with a sigh: 'Well, there are many religions, but I suppose they all worship the same God.' This remark kept me cheerful for about a week.

I also never would have imagined I'd quote back a church lesson, but when the rest of the crowd stood up to take communion, I found myself saying to Dimitri: "Don't you think that if God can supposedly forgive you, it's kind of egotistical for you not to forgive yourself?" "How long have you been waiting to use that line on me?" he asked. "Actually, it just came to me. Pretty good, huh? I bet you thought I wasn't paying attention." "You weren't. You never do. You were watching me.

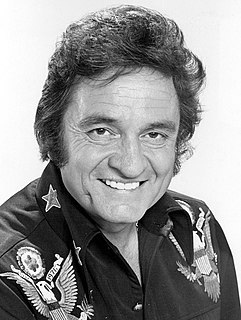

I had a song called "Folsom Prison Blues" that was a hit just before "I Walk The Line." And the people in Texas heard about it at the state prison and got to writing me letters asking me to come down there. So I responded and then the warden called me and asked if I would come down and do a show for the prisoners in Texas.

Somebody talked me into writing an autobiography about six or seven years ago. And I said I'd try. We talked into a tape recorder, and after a couple of months, I said, To hell with it. I was so depressed. It was like saying, 'This is the end.' I was more interested in what the hell was coming the next day or the next week.

I was once being interviewed by Barbara Walters. In between two of the segments she asked me: "But what would you do if the doctor gave you only six months to live?" I said, "Type faster." This was widely quoted, but the "six months" was changed to "six minutes," which bothered me. It's "six months."

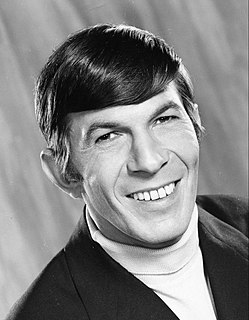

There was a very small crowd - minuscule compared to the crowd that he gathered later - at a private home in Los Angeles. And we were standing on the back patio, waiting for him. And he came through the house, saw me and immediately put his hand up in the Vulcan gesture. He said, 'They told me you were here.' We had a wonderful, brief conversation and I said, 'It would be logical if you would become president.'

Someone is always at my elbow reminding me that I am the grand-daughter of slaves. It fails to register depression with me. Slaver y is sixty years in the past. The operation was successful and the patient is doing well, thank you. The terrible struggle that made me an American out of a potential slave said "On the line!" The Reconstruction said "Go!" I am off to a flying start and I must not halt in the stretch to look behind and weep.