A Quote by Anne Bronte

And why should he interest himself at all in my moral and intellectual capacities: what is it to him what I think and feel?' I asked myself. And my heart throbbed in answer to the question.

Related Quotes

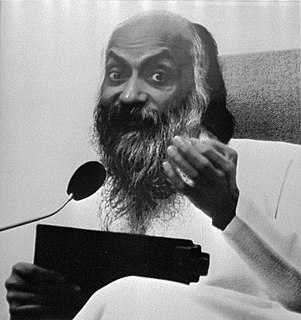

If you have a little inteligence, sooner or later the question is bound to arise: What is the point of it all? Why? It is impossible to avoid the question for long. And if you are very intelligent, it is always there, persistently there, hammering on your heart for the answer: Give me the answer! - Why?

It's the most annoying question and they just can't help asking you. You'll be asked it at family gatherings, weddings, and on first dates. And you'll ask yourself far too often. It's the question that has no good answer. It's the question that when people stop asking it, you'll feel even worse. - WHY ARE YOU SINGLE?

For a very great many years, I asked this question: ‘To communicate or not to communicate?’ If one got himself in such thorough trouble by communication, then of course one should stop communicating. But this is not the case. If one gets himself into trouble by communicating, he should further communicate. More communication, not less, is the answer.

How could it be that I had a legal obligation to kill people I did not know, and who did certainly not consent to it, while my father's doctor could not help my father to die when my farther asked for it? My consternation brought me to moral philosophy and a life-long search for an answer to the question when and why we should, and when we shouldn't, kill.

In the Marquette Lecture volume, I focus on the question in the title. I emphasize the social and political costs of being a Christian in the earliest centuries, and contend that many attempts to answer the question are banal. I don't attempt a full answer myself, but urge that scholars should take the question more seriously.

What is bad? What is good? What should one love, what hate? Why live, and what am I? What is lie,what is death? What power rules over everything?" he asked himself. And there was no answer to any of these questions except one, which was not logical and was not at all an answer to these questions. This answer was: "You will die--and everything will end. You will die and learn everything--or stop asking.

I have been asked so many times why I live a green life, why water conservation, why getting wells in places, why work with water organizations, why conserve water at home with double-flush toilets, why I tell my daughters, "Turn off the tap" so much. Sometimes I want to say, "I wish I knew the answer." My answer really is: I don't understand why everyone doesn't feel this way.

The great object of Education should be commensurate with the object of life. It should be a moral one; to teach self-trust: to inspire the youthful man with an interest in himself; with a curiosity touching his own nature; to acquaint him with the resources of his mind, and to teach him that there is all his strength.

When I decided to write about my brother and friends, I was attempting to answer the question why. Why did they all die like that? Why so many of them? Why so close together? Why were they all so young? Why, especially, in the kinds of places where we are from? Why would they all die back to back to back to back? I feel like I was writing my way towards an answer in the memoir.