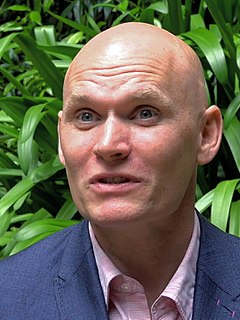

A Quote by Anthony Doerr

Science and literature are both ways to ask questions about why we're here.

Related Quotes

You can imagine over very long timescales, perhaps far beyond the multi-decade time scale, we might be able to ask very deep questions about why we feel the way we feel about things, or why we think of ourselves in certain ways - questions that have been in the realm of psychology and philosophy but have been very difficult to get a firm mechanistic laws-of-physics grasp on.

The book Forest Dark wants to provoke questions about what is reality and why are we so given to believe that reality is firm and unbendable. There's a whole host of questions that the book is asking about that. Why do we believe that the world is only one way and as we see it? Why are we not open to the ways in which it might be otherwise.

The mathematical question is "Why?" It's always why. And the only way we know how to answer such questions is to come up, from scratch, with these narrative arguments that explain it. So what I want to do with this book is open up this world of mathematical reality, the creatures that we build there, the questions that we ask there, the ways in which we poke and prod (known as problems), and how we can possibly craft these elegant reason-poems.

Systematic theology will ask questions like "What are the attributes of God? What is sin? What does the cross achieve?" Biblical theology tends to ask questions such as "What is the theology of the prophecy of Isaiah? What do we learn from John's Gospel? How does the theme of the temple work itself out across the entire Bible?" Both approaches are legitimate; both are important. They are mutually complementary.

We ask ourselves all kinds of questions, such as why does a peacock have such beautiful feathers, and we may answer that he needs the feathers to impress a female peacock, but then we ask ourselves, and why is there a peacock? And then we ask, why is there anything living? And then we ask, why is there anything at all? And if you tell some advocate of scientism that the answer is a secret, he will go white hot and write a book. But it is a secret. And the experience of living with the secret and thinking about it is in itself a kind of faith.

Are our ways of teaching students to ask some questions always correlative with our ways of teaching them not to ask - indeed, to be unconscious of - others? Does the educational system exist in order to promulgate knowledge, or is its main function rather to universalize a society’s tacit agreement about what it has decided it does not and cannot know?