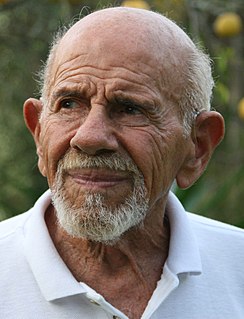

A Quote by Anthony Powell

The whole idea of interviews is in itself absurd - one cannot answer deep questions about what one's life was like - one writes novels about it.

Related Quotes

have a much harder time writing stories than novels. I need the expansiveness of a novel and the propulsive energy it provides. When I think about scene - and when I teach scene writing - I'm thinking about questions. What questions are raised by a scene? What questions are answered? What questions persist from scene to scene to scene?

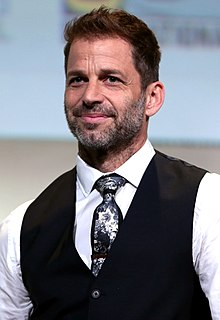

The cool thing about Watchmen is it has this really complicated question that it asks, which is: who polices the police or who governs the government? Who does God pray to? Those are pretty deep questions but also pretty fun questions. Kind of exciting. It tries to subvert the superhero genre by giving you these big questions, moral questions. Why do you think you're on a fun ride? Suddenly you're like how am I supposed to feel about that?

Intelligent, heartfelt stories that tell a whole new set of truths about growing up American. Julie Orringer writes with virtuosity and depth about the fears, cruelties, and humiliations of childhood, but then does that rarest, and more difficult, thing: writes equally beautifully about the moments of victory and transcendence.