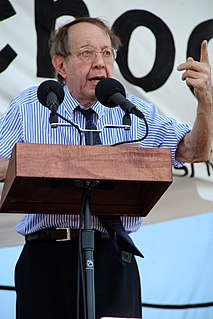

A Quote by Antonia Fraser

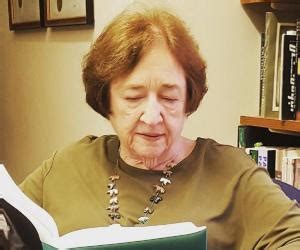

I am re-reading Henry James as a change from history. I began with Daisy Miller, and I've just finished Washington Square. What a brilliant, painful book.

Related Quotes

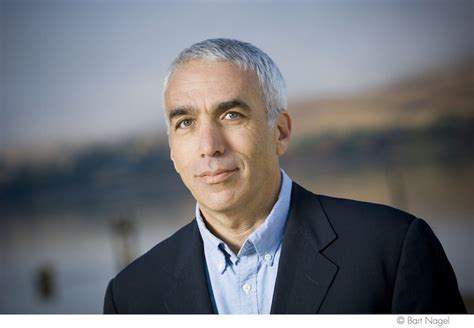

While reading writers of great formulatory power — Henry James, Santayana, Proust — I find I can scarcely get through a page without having to stop to record some lapidary sentence. Reading Henry James, for example, I have muttered to myself, "C’mon, Henry, turn down the brilliance a notch, so I can get some reading done." I may be one of a very small number of people who have developed writer’s cramp while reading.

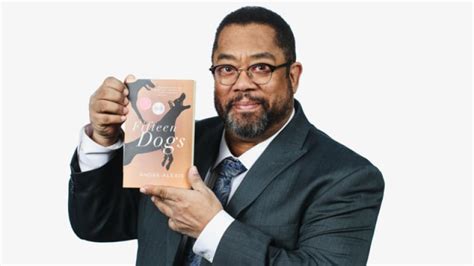

The book it reminded me of most is Henry Miller’s The Books in My Life. Like Miller, Shields manages to convey his affection for and admiration of literature, and that, the enthusiasm and admiration, can revitalize the reader’s love for the art form. I’m grateful for How Literature Saved My Life because the book has made me think again – and for the first time in a while – 'Well, what is it we do when we read?' It’s a damned annoying question, but it needs to be asked now and then, and Shields has asked it in a way I find resonant and moving.

I began writing books after speaking for several years and I realize that when you have a written book people think that you're smarter than you really are if I can joke. But it's interesting. People will buy your book and hire you without reading the book just because you have a book and you have a book on a subject that they think is of interest to themselves or e to their company.