A Quote by Antony Flew

Pascal makes no attempt in this most famous argument to show that his Roman Catholicism is true or probably true. The reasons which he suggests for making the recommended bet on his particular faith are reasons in the sense of motives rather than reasons in the sense of grounds. Conceding, if only for the sake of the present argument, that we can have no knowledge here, Pascal tries to justify as prudent a policy of systematic self-persuasion, rather than to provide grounds for thinking that the beliefs recommended are actually true.

Related Quotes

If it were true that conservatives were racist, sexist, homophobic, fascist, stupid, inflexible, angry, and self-righteous, shouldn't their arguments be easy to deconstruct? Someone who is making a point out of anger, ideology, inflexibility, or resentment would presumably construct a flimsy argument. So why can't the argument itself be dismembered rather than the speaker's personal style or hidden motives? Why the evasions?

We cannot ultimately specify the grounds (either metaphysical or logical or empirical) upon which we hold that our knowledge is true. Being committed to such grounds, dwelling in them, we are projecting ourselves to what we believe to be true from or through these grounds. We cannot therefore see what they are. We cannot look at them because we are looking with them.

Any comprehensive doctrine, religious or secular, can be introduced into any political argument at any time, but I argue that people who do this should also present what they believe are public reasons for their argument. So their opinion is no longer just that of one particular party, but an opinion that all members of a society might reasonably agree to, not necessarily that they would agree to. What's important is that people give the kinds of reasons that can be understood and appraised apart from their particular comprehensive doctrines.

Some care is needed in using Descartes' argument. "I think, therefore I am" says rather more than is strictly certain. It might seem as though we are quite sure of being the same person to-day as we were yesterday, and this is no doubt true in some sense. But the real Self is as hard to arrive at as the real table, and does not seem to have that absolute, convincing certainty that belongs to particular experiences.

It is when we create things for God's sake that our work most clearly promotes His glory, rather than threatening to compete with it. Thus the true purpose of art is the same as the true purpose of anything: it is not for ourselves or for our own self-expression, but for the service of others and the glory of God.

Kafka often describes himself as a bloodless figure: a human being who doesn't really participate in the life of his fellow human beings, someone who doesn't actually live in the true sense of the word, but who consists rather of words and literature. In my view, that is, however, only half true. In a roundabout way through literature, which presupposes empathy and exact observation, he immerses himself again in the life of society; in a certain sense he comes back to it.

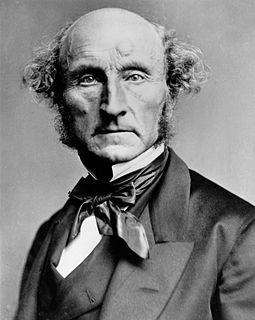

He who knows only his own side of the case (argument) knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side, if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion

The blessed Paul argues that we are saved by faith, which he declares to be not from us but a gift from God. Thus there cannot possibly be true salvation where there is no true faith, and, since this faith is divinely enabled, it is without doubt bestowed by his free generosity. Where there is true belief through true faith, true salvation certainly accompanies it. Anyone who departs from true faith will not possess the grace of true salvation.

=> When life gives you a hundred reasons to cry, show life that you have a thousand reasons to smile. => Never tell your problems to anyone...20% don't care and the other 80% are glad you have them. => It's true that we don't know what we've got until we lose it, but it's also true that we don't know what we've been missing until it arrives.

Try to find someone with a sense of humor. That's an important thing to have because when you get into an argument, one of the best ways to diffuse it is to be funny. You don't want to hide away from a point, because some points are serious, but you'd rather have a discussion that was a discussion, rather than an argument.