A Quote by Arthur Frederick Saunders

True beauty is in the mind; and the expression of the features depends more upon the moral nature than most persons are accustomed to think.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

Though beauty is, with the most apt similitude, I had almost said with the most literal truth, called a flower that fades and dies almost in the very moment of its maturity; yet there is, methinks, a kind of beauty which lives even to old age; a beauty that is not in the features, but, if I may be allowed the expression, shines through them. As it is not merely corporeal it is not the object of mere sense, nor is it to be discovered but by persons of true taste and refined sentiment.

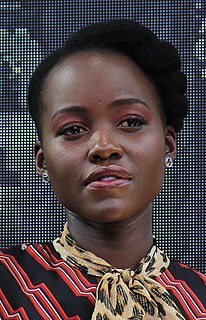

I come from a loving, supportive family, and my mother taught me that there are more valuable ways to achieve beauty than just through your external features. She was focused on compassion and respect, and those are the things that ended up translating to me as beauty. Beautiful people have many advantages, but so do friendly people.... I think beauty is an expression of love.

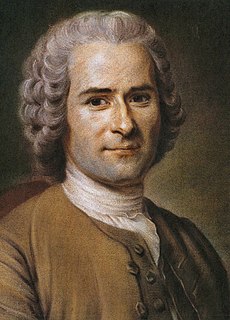

It is believed that physiognomy is only a simple development of the features already marked out by nature. It is my opinion, however, that in addition to this development, the features come insensibly to be formed and assume their shape from the frequent and habitual expression of certain affections of the soul. These affections are marked on the countenance; nothing is more certain than this; and when they turn into habits, they must leave on it durable impressions.

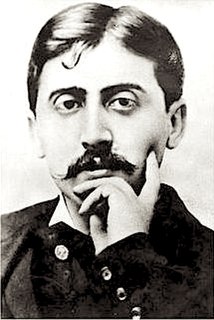

There are faces so fluid with expression, so flushed and rippled by the play of thought, that we can hardly find what the mere features really are. When the delicious beauty of lineament loses its power, it is because a more delicious beauty has appeared, that an interior and durable form has been disclosed.

We live in worlds that we have forged and composed. It's much more true than any of the species that you see. I mean, it seems to me that one of the most distinctive features of human intelligence is the capacity to imagine, to project out of our own immediate circumstances and to bring to mind things that aren't present here and now.

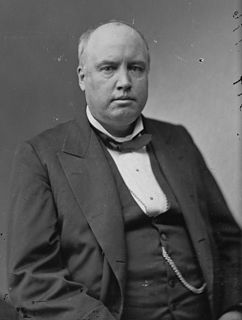

Art itself is essentially ethical; because every true work of art must have a beauty or grandeur of some kind, and beauty and grandeur cannot be comprehended by the beholder except through the moral sentiment. The eye is only a witness; it is not a judge. The mind judges what the eye reports to it; therefore, whatever elevates the moral sentiment to the contemplation of beauty and grandeur is in itself ethical.