A Quote by Ash Sarkar

Bengal in the early 1930s was a hotbed of anti-British revolutionary activity - and women were at the heart of this insurrectionist moment.

Related Quotes

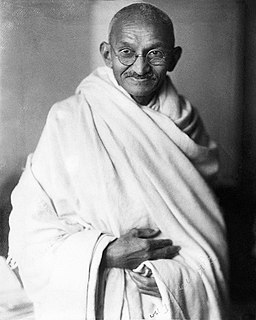

Ho Chi Minh was well aware that the enemy possessed more firepower than did his own forces, and sought to use what he viewed as the superior political and moral position of his own revolutionary movement as a trump card to defeat a well-armed adversary. These ideas were originally generated during his early years as a revolutionary in the 1920s and 1930s, and continued to influence his recommendations in the wars against the French (1946-1954) and the United States (1959-1965).

In the late 1930s, both the British and American movie industries made a succession of films celebrating the decency of the British Empire in order to challenge the threatening tide of Nazism and fascism and also to provide employment for actors from Los Angeles's British colony. The best two were Hollywood's Gunga Din and Britain's The Four Feathers...

Bombay is far ahead of Bengal in the matter of female education. I have visited some of the best schools in Bengal and Bombay, and I can say from my own experience that there are a larger number of girls receiving public education in Bombay than in Bengal; but while Bengal has not come up to Bombay as far as regarded extent of education, Bengal is not behind Bombay in the matter of solidarity and depth.

Over the years, my marks on paper have landed me in all sorts of courts and controversies - I have been comprehensively labelled; anti-this and anti-that, anti-social, anti-football, anti-woman, anti-gay, anti-Semitic, anti-science, anti-republican, anti-American, anti-Australian - to recall just an armful of the antis.

Who wouldn't want to vote for a guy who was a peaceful, radical, non-violent revolutionary; who hung around with lepers, hookers, and crooks; who never spoke English; was not an American citizen; anti-capitalism; totally anti-death penalty; anti-public prayer (Matthew 6:5); but never once anti-gay; didn't mention abortion; and was a long-haired, brown-skinned, homeless, middle-eastern, Jew?

In the wars against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France, as in so many later conflicts, British women seem to have been no more markedly pacifist than men. Instead, and exactly like so many of their male countrymen, some women found ways of combining support for the national interest with a measure of self-promotion. By assisting the war effort, women demonstrated that their concerns were by no means confined to the domestic sphere. Under cover of a patriotism that was often genuine and profound, they carved out for themselves a real if precarious place in the public sphere.