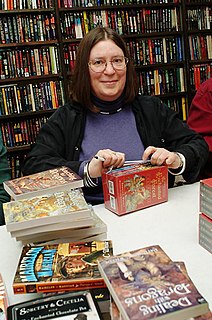

A Quote by Ayelet Waldman

The Q I loathe and despise, the Q every single writer I know loathes and despises, is this one: 'Where,' the reader asks, 'do you get your ideas?' It's a simple question, and my usual response is a kind of helpless, 'I don't know.'

Related Quotes

Your mind, in order to defend itself starts to give life to inanimate objects. When that happens it solves the problem of stimulus and response because literally if you're by yourself you lose the element of stimulus and response. Somebody asks a question, you give a response. So, when you lose the stimulus and response, what I connected to is that you actually create all the stimulus and response.

Every writer knows that when you're imitating somebody - you know, you're sounding like Faulkner - you're doing pretty good, but your life in Hoboken isn't Faulkneresque. So you get that kind of shortfall between the actual experience of the writer and the things he's hungry to express and the voice itself.

"Where do you get your ideas?" That's the one question I'm genuinely sick of being asked, and also genuinely fascinated by. What fascinates me is not that people ask the question, but what kind of answer are they really looking for? Because if I tell them the truth, which is "I make them up," they seem very disappointed. They want to know about the trek I do once a year to the mountain.

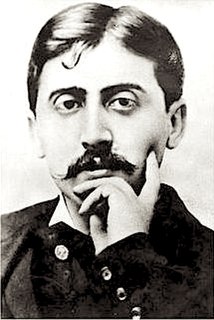

Every reader, as he reads, is actually the reader of himself. The writer's work is only a kind of optical instrument he provides the reader so he can discern what he might never have seen in himself without this book. The reader's recognition in himself of what the book says is the proof of the book's truth.