A Quote by B. C. Forbes

A willing, cheerful worker, with his heart in his job, will turn out more work and more satisfactory work in 44 hours than an unwilling worker, dissatisfied with his conditions, will turn out in 54 hours. It is good business, therefore, for every employer to go as far as he possibly can in reaching a schedule agreeable to his people.

Related Quotes

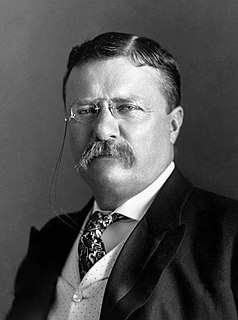

There is nothing a worker resents more than to see some man taking his job. A factory can be closed down, its chimneys smokeless, waiting for the worker to come back to his job, and all will be peaceful. But the moment workers are imported, and the striker sees his own place usurped, there is bound to be trouble.

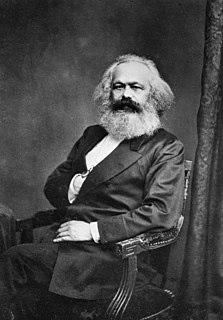

The fact that labour is external to the worker, i.e., it does not belong to his intrinsic nature; that in his work, therefore he does not affirm himself but denies himself, does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and his mind. The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself.

What Qatar chose is a system where a worker is owned by his employer. When your employer forces you to live in squalor, makes you work longest hours in extreme heat, doesn't allow you to change jobs, doesn't pay your wages on time, abuses you physically and psychologically, you have no way out, you can't leave. You are trapped.

In doing one's work primarily for God, the fear of undue restriction is put, sooner or later, out of the question. He pays me and He pays me well. He pays me and He will not fail to pay me. He pays me not merely for the rule of thumb task, which is all that men recognize, but to everything else I bring to my job in the way of industry, good intentions and cheerfulness. If the Lord loveth a cheerful giver, as St. Paul says, we may depend upon it that He loveth a cheerful worker; and where we can cleave the way to His love there we find His endless generosity.

It should be the privilege of every worker to take advantage of all the improved methods of working that relieve him from the tedium and fatigue of purely mechanical toil, for by this means he gains leisure for the thought necessary to working out his designs, and for the finer touches that the hand alone can give. So long as he remains master of his machinery it will serve him well, and his power of artistic expression will be freed rather than stifled by turning over to it work it is meant to do.

There is no employing class, no working class, no farming class. You may pigeonhole a man or woman as a farmer or a worker or a professional man or an employer or even a banker. But the son of the farmer will be a doctor or a worker or even a banker, and his daughter a teacher. The son of a worker will be an employer - or maybe president.

My role models are people who can do things; I say to myself, "I wish I could do that." Like women who endure hardships and turn their luck around and bring up children on their own and start a business. Or a social worker who leaves his country, his comfort, his friends, and goes far away to help people he doesn't know. I want to evolve into that, ultimately. I want to be that person who could sacrifice everything for others.

A foreign minister, I will maintain it, can never be a good man of business if he is not an agreeable man of pleasure too. Half his business is done by the help of his pleasures: his views are carried on, and perhaps best, and most unsuspectedly, at balls, suppers, assemblies, and parties of pleasure; by intrigues with women, and connections insensibly formed with men, at those unguarded hours of amusement.