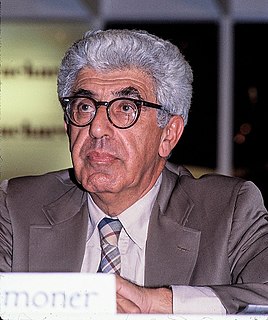

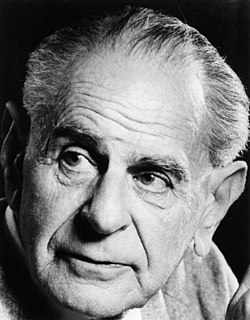

A Quote by Barry Commoner

The age of innocent faith in science and technology may be over.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

Science fiction is fantasy about issues of science. Science fiction is a subset of fantasy. Fantasy predated it by several millennia. The '30s to the '50s were the golden age of science fiction - this was because, to a large degree, it was at this point that technology and science had exposed its potential without revealing the limitations.

I believe in rendering to science the things that belong to science. I have no problem with evolution or discussions of the age of the Earth, for I don't believe that we come anywhere near comprehending the mind of God or the workings of the universe. Science can explain a lot, but it cannot give us faith, and I think we need both.

But science can only be created by those who are thoroughly imbued with the aspiration toward truth and understanding. This source of feeling, however, springs from the sphere of religion. To this there also belongs the faith in the possibility that the regulations valid for the world of existence are rational, that is, comprehensible to reason. I cannot conceive of a genuine scientist without that profound faith. The situation may be expressed by an image: science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind.

Science has only two things to contribute to religion: an analysis of the evolutionary, cultural, and psychological basis for believing things that aren't true, and a scientific disproof of some of faith's claims (e.g., Adam and Eve, the Great Flood). Religion has nothing to contribute to science, and science is best off staying as far away from faith as possible. The "constructive dialogue" between science and faith is, in reality, a destructive monologue, with science making all the good points, tearing down religion in the process.

May I make two citations from the words of a discerning editorial writer, not one of my faith, but one of much faith: "If we neglect the divine . . . and give ourselves over wholly to the human," he said, "we may certainly count upon nothing but the triumph of pessimism. . . . True optimism must rest upon a calm, unshakable faith in eternal life and in the unlimited goodness of him who gives it."