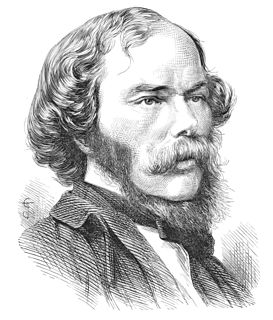

A Quote by Baruch Spinoza

Further conceive, I beg, that a stone, while continuing in motion, should be capable of thinking and knowing, that it is endeavoring, as far as it can, to continue to move. Such a stone, being conscious merely of its own endeavor and not at all indifferent, would believe itself to be completely free, and would think that it continued in motion solely because of its own wish. This is that human freedom, which all boast that they possess, and which consists solely in the fact, that men are conscious of their own desire, but are ignorant of the causes whereby that desire has been determined.

Quote Topics

As Far As

Because

Been

Beg

Being

Believe

Boast

Capable

Causes

Conceive

Conscious

Consists

Continue

Continuing

Desire

Determined

Endeavor

Fact

Far

Free

Freedom

Further

Human

Human Freedom

Ignorant

Indifferent

Itself

Knowing

Men

Merely

Motion

Move

Own

Possess

Should

Solely

Stone

Think

Thinking

Which

While

Wish

Would

Would Be

Related Quotes

But although the attractive virtue of the earth extends upwards, as has been said, so very far, yet if any stone should be at a distance great enough to become sensible compared with the earth's diameter, it is true that on the motion of the earth such a stone would not follow altogether; its own force of resistance would be combined with the attractive force of the earth, and thus it would extricate itself in some degree from the motion of the earth.

Every thing thinks, but according to its complexity. If this is so, then stones also think...and this stone thinks only I stone, I stone, I stone. But perhaps it cannot even say I. It thinks: Stone, stone, stone... God enjoys being All, as this stone enjoys being almost nothing, but since it knows no other way of being, it is pleased with its own way, eternally satisfied with itself.

Compared with the person who is conscious of his despair, the despairing individual who is ignorant of his despair is simply a negativity further away from the truth and deliverance. . . . Yet ignorance is so far from breaking the despair or changing despair to nondespairing that it can in fact be the most dangerous form of despair. . . . An individual is furthest from being conscious of himself as spirit when he is ignorant of being in despair. But precisely this-not to be conscious of oneself as spirit-is despair, which is spiritlessness. . . .

Whatever is in motion must be put in motion by another. If that by which it is put in motion be itself put in motion, then this also must needs be put in motion by another, and that by another again. But this cannot go on to infinity, because then there would be no first mover, and, consequently, no other mover; seeing that subsequent movers move only inasmuch as they are put in motion by the first mover; as the staff moves only because it is put in motion by the hand. Therefore it is necessary to arrive at a first mover, put in motion by no other; and this everyone understands to be God.

It is what makes conscious of the conditions and laws of observing which applied in this manner become a theme on its own. The activity of consciousness depending on the way the work itself proceeds, becomes the subject of my attention this way and it is precisely because of this voyeuristic attitude toward the own observation and experience of the subject that the conscious analytic dimension in the work shows.

If the concept of consciousness were to fall to science, what would happen to our sense of moral agency and free will? If conscious experience were reduced somehow to mere matter in motion, what would happen to our appreciation of love and pain and dreams and joy? If conscious human beings were just animated material objects, how could anything we do to them be right or wrong?

Men are apt to mistake, or at least to seem to mistake, their own talents, in hopes, perhaps, of misleading others to allow them that which they are conscious they do not possess. Thus lord Hardwicke valued himself more upon being a great minister of state, which he certainly was not, than upon being a great magistrate, which he certainly was.