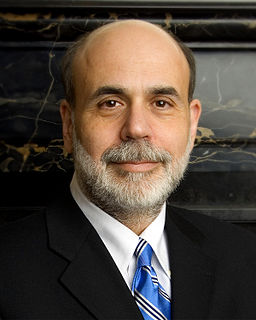

A Quote by Ben Bernanke

After a long period in which the desired direction for inflation was always downward, the industrialized world's central banks must today try to avoid major changes in the inflation rate in either direction.

Related Quotes

Significant changes in the growth rate of money supply, even small ones, impact the financial markets first. Then, they impact changes in the real economy, usually in six to nine months, but in a range of three to 18 months. Usually in about two years in the US, they correlate with changes in the rate of inflation or deflation."

"The leads are long and variable, though the more inflation a society has experienced, history shows, the shorter the time lead will be between a change in money supply growth and the subsequent change in inflation.

The unique aspect of today's monetary inflation is that it is not limited to one country, but a host of countries are all inflating together. As a result of the monetary inflation (when all of the newly created money begins to leave the banks and enter the system), the price inflation will be worldwide.

It’s hard to build models of inflation that don't lead to a multiverse. It’s not impossible, so I think there’s still certainly research that needs to be done. But most models of inflation do lead to a multiverse, and evidence for inflation will be pushing us in the direction of taking [the idea of a] multiverse seriously.

It is a sobering fact that the prominence of central banks in this century has coincided with a general tendency towards more inflation, not less. [I]f the overriding objective is price stability, we did better with the nineteenth-century gold standard and passive central banks, with currency boards, or even with 'free banking.' The truly unique power of a central bank, after all, is the power to create money, and ultimately the power to create is the power to destroy.

So: if the chronic inflation undergone by Americans, and in almost every other country, is caused by the continuing creation of new money, and if in each country its governmental "Central Bank" (in the United States, the Federal Reserve) is the sole monopoly source and creator of all money, who then is responsible for the blight of inflation? Who except the very institution that is solely empowered to create money, that is, the Fed (and the Bank of England, and the Bank of Italy, and other central banks) itself?