A Quote by Benito Mussolini

You know what I think about violence. For me it is profoundly moral -more moral than compromises and transactions.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

Not one idiot in a thousand has been entirely refractory to treatment, not one in a hundred has not been made more happy and healthy; more than thirty per cent have been taught to conform to social and moral law, and rendered capable of order, of good feeling, and of working like the third of a man; more than forty per cent have become capable of the ordinary transactions of life under friendly control, of understanding moral and social abstractions, of working like two-thirds of a man.

If I were to speak your kind of language, I would say that man's only moral commandment is: Thou shalt think.

But a 'moral commandment' is a contradiction in terms. The moral is the chosen, not the forced; the understood, not the obeyed.

The moral is the rational, and reason accepts no commandments.

Political realism is aware of the moral significance of political action. It is also aware of the ineluctable tension between the moral command and the requirements of successful political action. And it is unwilling to gloss over and obliterate that tension and thus to obfuscate both the moral and the political issue by making it appear as though the stark facts of politics were morally more satisfying than they actually are, and the moral law less exacting than it actually is.

The foundation of leadership is your own moral compass. I think the best quality leaders really know where their moral compass is. They get it out when they are making decisions. It's their guide. But not only do you have to have a moral compass and take it out of your pocket, it has to have a true north.

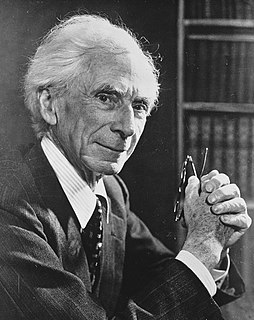

The objections to religion are of two sorts - intellectual and moral. The intellectual objection is that there is no reason to suppose any religion true; the moral objection is that religious precepts date from a time when men were more cruel than they are and therefore tend to perpetuate inhumanities which the moral conscience of the age would otherwise outgrow.

If you speak [ about violence against Israelis], you are in an unspeakable place, have become a Nazi or its moral equivalent (if there is a moral equivalent). It certainly terrifies, but perhaps also it is a linguistic permutation of state terrorism, an assault that stops one in one's tracks, and secures the continuing operation of the regime and its monopoly on politically intelligible speech.