A Quote by Betty Edwards

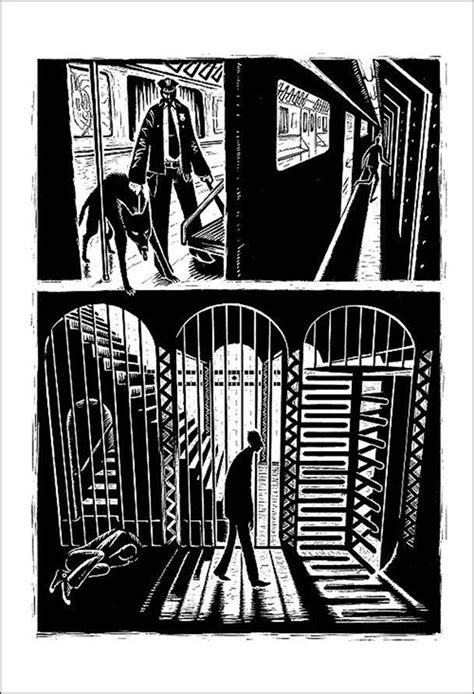

Art has this long history, predating even language, of expressing nonverbal information.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

Imagine it's 1981. You're an artist, in love with art, smitten with art history. You're also a woman, with almost no mentors to look to; art history just isn't that into you. Any woman approaching art history in the early eighties was attempting to enter an almost foreign country, a restricted and exclusionary domain that spoke a private language.

Rather than thinking of sound and sense in my essays as two opposing principles, two perpendicular trajectories, as they are often considered in conversations around translation, or even as two disassociated phenomena that can be brought together to collaborate with more or less success, I think of sound as sense. Sound has its own meaning, and it's one of the many non-semantic dimensions of meaning in language. I want to emphasize is the formal dynamic between language-as-information and language-as-art-material.

Predating the Internet and predating videos, you had an active imagination. You would hear sounds and then get mental pictures of what these sounds felt like to you. It engaged you and made you more invested in it. It made you want to get tickets to the show, buy the album, put the poster on the wall. Now it's sensory overload.

We hypostatize information into objects. Rearrangement of objects is change in the content of the information; the message has changed. This is a language which we have lost the ability to read. We ourselves are a part of this language; changes in us are changes in the content of the information. We ourselves are information-rich; information enters us, is processed and is then projected outward once more, now in an altered form. We are not aware that we are doing this, that in fact this is all we are doing.

I think that I would really like at first for the art to speak for itself. I don't see the need for a lot of personal information about my past or who I am. I would rather the personal side of it just be in the concepts and the genuine feelings that I filter through my work. I know that it's inevitable that people can find whatever they want about me. Once I've had a chance to create a language and a world with my art, then I'm more comfortable sharing that information.