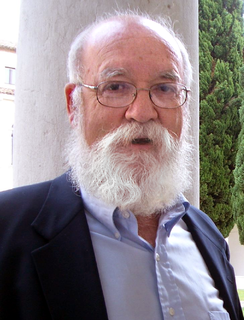

A Quote by Bill Ayers

We have arguments [with my father] and we had a lot of arguments in the years when I was at Michigan.

Related Quotes

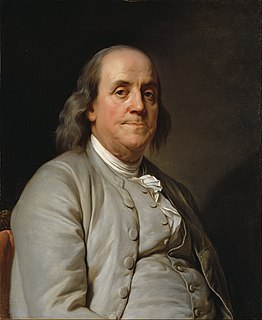

I am well acquainted with all the arguments against freedom of thought and speech - the arguments which claim that it cannot exist, and the arguments which claim that it ought not to. I answer simply that they don't convince me and that our civilization over a period of four hundred years has been founded on the opposite notice.

Highly technical philosophical arguments of the sort many philosophers favor are absent here. That is because I have a prior problem to deal with. I have learned that arguments, no matter how watertight, often fall on deaf ears. I am myself the author of arguments that I consider rigorous and unanswerable but that are often not such much rebutted or even dismissed as simply ignored.

When confronted with two courses of action I jot down on a piece of paper all the arguments in favor of each one, then on the opposite side I write the arguments against each one. Then by weighing the arguments pro and con and cancelling them out, one against the other, I take the course indicated by what remains.

We go to the opening arguments or the closing arguments of a case, and we'd see which actor got the big one. I had a seven-page one once which just about killed me, and I thought, 'Oh, I'm going to get fired, that's it, I can't do it.' It was like a one-act play, and I had a few weeks to learn it, luckily. But it's terrifying.