A Quote by Blaise Pascal

There are hardly any truths upon which we always remain agreed, and still fewer objects of pleasure which we do not change every hour, I do not know whether there is a means of giving fixed

rules for adapting discourse to the inconstancy of our caprices.

Related Quotes

Our initial sensory data are always "first derivatives," statements about differences which exist among external objects or statements about changes which occur either in them or in our relationship to them. Objects and circumstances which remain absolutely constant relative to the observer, unchanged either by his own movement or by external events, are in general difficult and perhaps always impossible to perceive. What we perceive easily is difference and change and difference is a relationship.

All these stupendous objects are daily around us; but because they are constantly exposed to our view, they never affect our minds, so natural is it for us to admire new, rather than grand objects. Therefore the vast multitude of stars which diversify the beauty of this immense body does not call the people together; but when any change happens therein, the eyes of all are fixed upon the heavens.

Even where the affections are not strongly moved by any superior excellence, the companions of our childhood always possess a certain power over our minds which hardly any later friend can obtain. They know our infantine dispositions, which, however they may be afterwards modified, are never eradicated; and they can judge of our actions with more certain conclusions as to the integrity of our motives.

...our life crises tell us that we need to break free of beliefs that no longer serve our personal development.

These points at which we must choose to change or to stagnate are our greatest challenges.

Every new crossroads means we enter into a new cycle of change - whether it be adopting a new health regimen or a new spiritual practice.

And change inevitably means letting go of familiar people and places and moving on to another stage of life.

You see, in our family we don't know whether we're coming or going - it's all my grandmother's fault. But, of course, the fault wasn't hers at all: it lay in language. Every language assumes a centrality, a fixed and settled point to go away from and come back to, and what my grandmother was looking for was a word for a journey which was not a coming or a going at all; a journey that was a search for precisely that fixed point which permits the proper use of verbs of movement.

Education may well be, as of right, the instrument whereby every individual, in a society like our own, can gain access to any kind of discourse. But we well know that in its distribution, in what it permits and in what it prevents, it follows the well-trodden battle-lines of social conflict. Every educational system is a political means of maintaining or of modifying the appropriation of discourse, with the knowledge and the powers it carries with it.

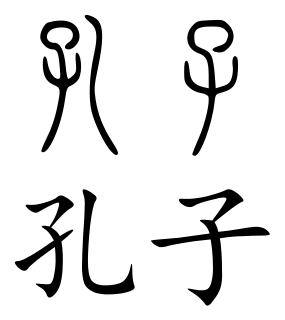

Know that for the human mind there are certain objects of perception which are within the scope of its nature and capacity; on the other hand, there are, amongst things which actually exist, certain objects which the mind can in no way and by no means grasp: the gates of perception are closed against it.

The entire routine of our memorized acquisitions, for example, is a consequence of nothing but the Law of Contiguity. The words of a poem, the formulas of trigonometry, the facts of history, the properties of material things, are all known to us as definite systems or groups of objects which cohere in an order fixed by innumerable iterations, and of which any one part reminds us of the others.

the usual attitude of Christians towards Jews is - I hardly know whether to say more impious or more stupid, when viewed in the light of their professed principles. ... They hardly know Christ was a Jew. And I find men, educated, supposing that Christ spoke Greek. To my feeling, this deadness to the history which has prepared half our world for us, this inability to find interest in any form of life that is not clad in the same coat-tails and flounces as our own, lies very close to the worst kind of irreligion.