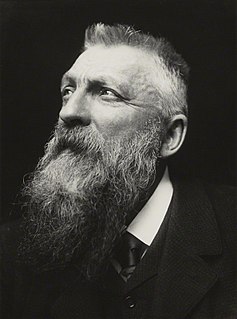

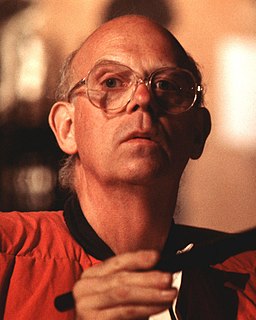

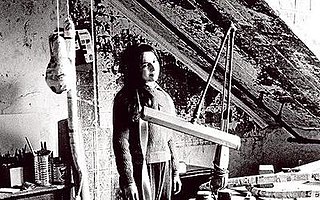

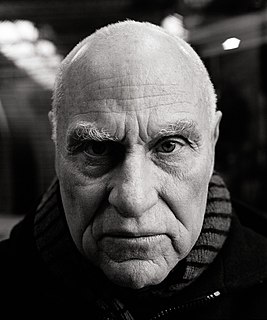

A Quote by Christian Boltanski

The photo replaces the memory. When someone dies, after a while you can't visualize them anymore, you only remember them through their pictures.

Related Quotes

For 10 days after the Olympics, I couldn't go back to my house because people were sitting outside waiting to take my photo. That was a bit rubbish. At first I was open: 'Yeah, of course you can take a photo...' but after a while, it got to the point where I thought, 'Whoa, I don't like this attention anymore.'

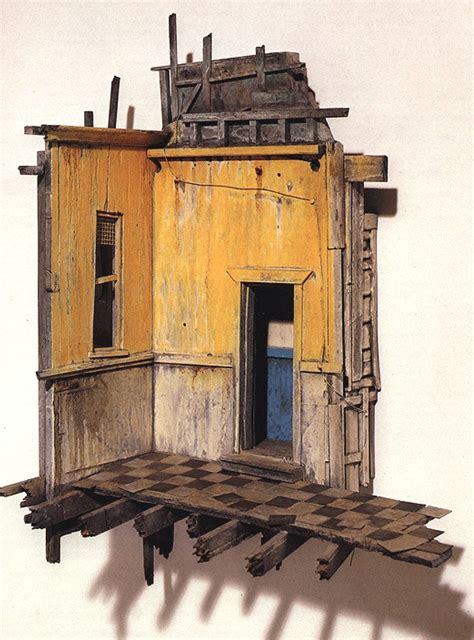

We buy things. We wear them or put them on our walls, or sit on them, but anyone who wants to can take them away from us. Or break them.

...

Long after he's dead, someone else will own those stupid little boxes, and then someone after him, just as someone owned them before he did. But no one ever thinks of that: objects survive us and go on living. It's stupid to believe we own them. And it's sinful for them to be so important.

The happening and telling are very different things. This doesn’t mean that the story isn’t true, only that I honestly don’t know anymore if I really remember it or only remember how to tell it. Language does this to our memories, simplifies, solidifies, codifies, mummifies. An off-told story is like a photograph in a family album. Eventually it replaces the moment it was meant to capture.

But pain may be a gift to us. Remember, after all, that pain is one of the ways we register in memory the things that vanish, that are taken away. We fix them in our minds forever by yearning, by pain, by crying out. Pain, the pain that seems unbearable at the time, is memory's first imprinting step, the cornerstone of the temple we erect inside us in memory of the dead. Pain is part of memory, and memory is a God-given gift.

Memory is therefore, neither Perception nor Conception, but a state or affection of one of these, conditioned by lapse of time. As already observed, there is no such thing as memory of the present while present, for the present is object only of perception, and the future, of expectation, but the object of memory is the past. All memory, therefore, implies a time elapsed; consequently only those animals which perceive time remember, and the organ whereby they perceive time is also that whereby they remember.

The books or the music in which we thought the beauty was located will betray us if we trust to them; it was not in them, it only came through them,and what came through them was longing. These things—the beauty, the memory of our own past—are good images of what we really desire; but if they are mistaken for the thing itself they turn into dumb idols,breaking the hearts of their worshippers. For they are not the thing itself; they are only the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news from a country we have never yet visited.

In the beginning [of my social media life], I started posting and someone I'm close to said, "you're only posting pictures of yourself in your grungy pajamas. You're an actress be aspirational." Then I was like, "I'm not living an aspirational life on a day-to-day basis." For a while after that I was only taking pictures of, like, objects.

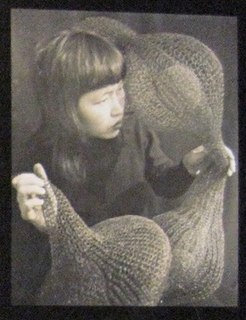

The "essence" of comics is fundamentally the weird process of reading pictures, not just looking at them. I see the black outlines of cartoons as visual approximations of the way we remember general ideas, and I try to use naturalistic color underneath them to simultaneously suggest a perceptual experience, which I think is more or less the way we actually experience the world as adults; we don't really "see" anymore after a certain age, we spend our time naming and categorizing and identifying and figuring how everything all fits together.