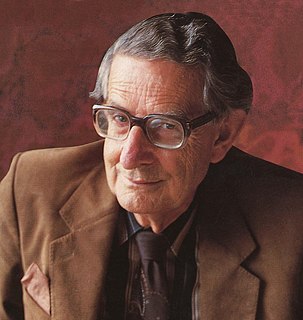

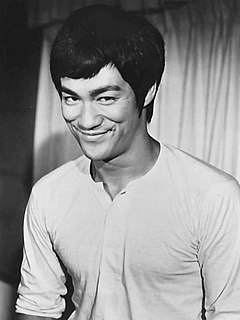

A Quote by Christopher Voss

The secret to gaining the upper hand in a negotiation is to give the other side the illusion of control. Don't try to force your opponent to admit that you are right. Ask questions, that begin with 'How?' or 'What?' so your opponent uses mental energy to figure out the answer.

Related Quotes

Before you even consider making a value bet, try to determine if the bet will have any value at all. Attempt to put your opponent on a hand that he'd likely call a bet with on the river. To do this, you'll have to mentally play back the details of the hand. Think about your opponent's playing tendencies.

When you go out on the court whether it be for the championship or just a scrimmage, have confidence that your abilities and what you've learned in your drills are better than your opponent's. This does not mean you should disregard your opponent. Before taking the court for any game, you should do a lot of thinking about what you have to do to beat your opponent and what he must or can do to beat you.

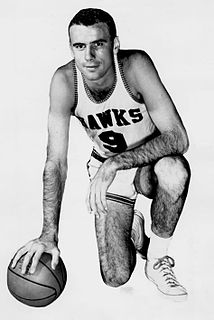

I believe that good defense embodies seven cardinal principle: reduce the number of your opponent's shots; force your opponent into low percentage shots; control everything within 18 feet; eliminate second shots; no easy baskets; point the ball on all long shots; and prevent the ball from going into the pivot man.

Our moral reasoning is plagued by two illusions. The first illusion can be called the wag-the-dog illusion: We believe that our own moral judgment (the dog) is driven by our own moral reasoning (the tail). The second illusion can be called the wag-theother-dog's-tail illusion: In a moral argument, we expect the successful rebuttal of an opponent's arguments to change the opponent's mind. Such a belief is like thinking that forcing a dog's tail to wag by moving it with your hand will make the dog happy.

Knowing your opponent is a crucial part of emulating and defeating that opponent. But scouting is only the first step. Too many leaders spend countless hours studying an opponent's every move in the search for an edge. The Great Teams understand not only how to scout but also how to exploit the weaknesses of a competitor. These teams analyze every perspective and option and position themselves to take full advantage of any knowledge gained about an opponent.

Ask your child for information in a gentle, nonjudgmental way, with specific, clear questions. Instead of “How was your day?” try “What did you do in math class today?” Instead of “Do you like your teacher?” ask “What do you like about your teacher?” Or “What do you not like so much?” Let her take her time to answer. Try to avoid asking, in the overly bright voice of parents everywhere, “Did you have fun in school today?!” She’ll sense how important it is that the answer be yes.