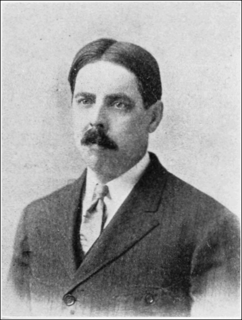

A Quote by Claude Levi-Strauss

With all its technical sophistication, the photographic camera remains a coarse device compared to the human hand and brain.

Related Quotes

The camera has a mind of its own--its own point of view. Then the human bearer of time stumbles into the camera's gaze--the camera's domain of pristine space hitherto untraversed is now contaminated by human temporality. Intrusion occurs, but the camera remains transfixed by its object. It doesn't care. The camera has no human fears.

Because we do not understand the brain very well we are constantly tempted to use the latest technology as a model for trying to understand it. In my childhood we were always assured that the brain was a telephone switchboard...Sherrington, the great British neuroscientist, thought the brain worked like a telegraph system. Freud often compared the brain to hydraulic and electromagnetic systems. Leibniz compared it to a mill...At present, obviously, the metaphor is the digital computer.

... what is faked [by the computerization of image-making], of course, is not reality, but photographic reality, reality as seen by the camera lens. In other words, what computer graphics have (almost) achieved is not realism, but rather only photorealism - the ability to fake not our perceptual and bodily experience of reality but only its photographic image.

Of course, the whole photographic process has been made much faster, cleaner and far more accessible to people by digital innovations, which is really great. Everybody now has a camera, often as part of our phone, and most of these cameras require little to no technical training. An enormous variety of apps also enable us to take short cuts to finished images. We hardly need to even think anymore.

I know that I make technical mistakes from time to time. It's one of the aspects of my game that I've been working on for years. I think I've managed to reduce the number of those technical mistakes to a minimum, but occasionally, they happen. On the other hand, I do have moments of technical brilliance.