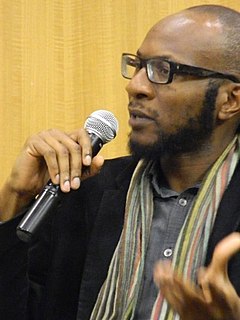

A Quote by Colson Whitehead

The idea of sacrifice is integral to the John Henry myth. Heroic figures have to die in order for us to have our stories; we live and stand on their bones.

Related Quotes

Perhaps this is what we mean by sanity: that, whatever our self-admitted eccentricities might be, we are not the villains of our own stories. In fact, it is quite the contrary: we play, and only play, the hero, and in the swirl of other people's stories, insofar as these stories concern us at all, we are never less than heroic.

Myth is the practical metabolism of our soulish life, the logic of our obsessions and oversights for which we have no language or code. Myth is the "morality" that the ineffable puts upon us, our unaccountable imperatives, our inexplicably selective clarity and obscurity, the mortal one-sidedness of our talents and wits, the passion and apathy that make such a transient passage through our hapless minds; that weave a pattern of fatality others will see before we do. Myth is distinctively human or sublime higher-order instinct, the "reason" in culture that reason knows not of.

Live Free or Die Hard may work better for an audience that doesn't know much about the series is than it will for Die Hard die hards, who will be wondering who that impersonator is and what he did with the real John McClane. The original Die Hard came out of nowhere to blitz the 1988 summer box office. The fourth installment arrives with a weight of expectations that Atlas would have trouble shouldering and, when the dust settles in September, it's unlikely that Live Free or Die Hard will be one of this year's big success stories.

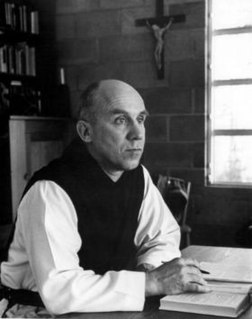

Our Christian destiny is, in fact, a great one: but we cannot achieve greatness unless we lose all interest in being great. For our own idea of greatness is illusory, and if we pay too much attention to it we will be lured out of the peace and stability of the being God gave us, and seek to live in a myth we have created for ourselves. And when we are truly ourselves we lose most of the futile self-consciousness that keeps us constantly comparing ourselves with others in order to see how big we are.

The Nigerian storyteller Ben Okri says that ‘In a fractured age, when cynicism is god, here is a possible heresy: we live by stories, we also live in them. One way or another we are living the stories planted in us early or along the way, or we are also living the stories we planted — knowingly or unknowingly — in ourselves. We live stories that either give our lives meaning or negate it with meaninglessness. If we change the stories we live by, quite possibly we change our lives.’

The storyteller is deep inside everyone of us. The story-maker is always with us. Let us suppose our world is attacked by war, by the horrors that we all of us easily imagine. Let us suppose floods wash through our cities, the seas rise . . . but the storyteller will be there, for it is our imaginations which shape us, keep us, create us - for good and for ill. It is our stories that will recreate us, when we are torn, hurt, even destroyed. It is the storyteller, the dream-maker, the myth-maker, that is our phoenix, that represents us at our best, and at our most creative.

Few of us will do the spectacular deeds of heroism that spread themselves across the pages of our newspapers in big black headlines. But we can all be heroic in the little things of everyday life. We can do the helpful things, say the kind words, meet our difficulties with courage and high hearts, stand up for the right when the cost is high, keep our word even though it means sacrifice, be a giver instead of a destroyer. Often this quiet, humble heroism is the greatest heroism of all.

It is a horrible idea that there is somebody who owns us, who makes us, who supervises us - waking and sleeping - who knows our thoughts, who can convict us of thought crime, thought crime, just for what we think, who can judge us while we sleep for things that might occur to us in our dreams, who can create us sick, as apparently we are - and then order us, on pain of eternal torture to be well again.

To demand this, to wish this to be true is to wish to live as an abject slave.