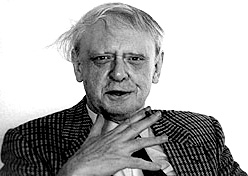

A Quote by Cynthia Ozick

With certain rapturous exceptions, literature is the moral life.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

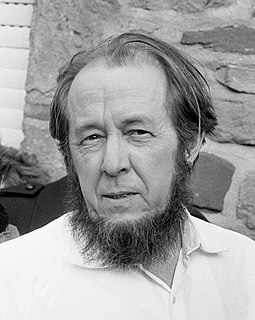

Literature cannot develop between the categories "permitted"—"not permitted"—"this you can and that you can't." Literature that is not the air of its contemporary society, that dares not warn in time against threatening moral and social dangers, such literature does not deserve the name of literature; it is only a facade. Such literature loses the confidence of its own people, and its published works are used as waste paper instead of being read. -Letter to the Fourth National Congress of Soviet Writers

We do literature a real disservice if we reduce it to knowledge or to use, to a problem to be solved. If literature solves problems, it does so by its own inexhaustibility, and by its ultimate refusal to be applied or used, even for moral good. This refusal, indeed, is literature's most moral act. At a time when meanings are manifold, disparate, and always changing, the rich possibility of interpretation--the happy resistance of the text to ever be fully known and mastered--is one of the most exhilarating products of human culture.

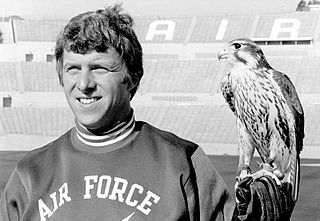

Part of buying the groceries is having a philosophy and trying to stick to it as best you can, knowing that occasionally you may make an exception. But, you do so knowing you're attempting to do it for a certain reason and you have to be very careful not to try to make too many exceptions, because then you wind up as a franchise with a team full of exceptions, which is not what you want.

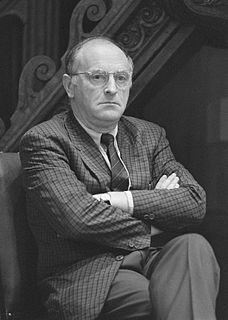

As a form of moral insurance, at least, literature is much more dependable than a system of beliefs or a philosophical doctrine. Since there are no laws that can protect us from ourselves, no criminal code is capable of preventing a true crime against literature; though we can condemn the material suppression of literature - the persecution of writers, acts of censorship, the burning of books - we are powerless when it comes to its worst violation: that of not reading the books. For that crime, a person pays with his whole life; if the offender is a nation, it pays with its history.

Whether moral and social phenomena are really exceptions to the general certainty and uniformity of the course of nature; and how far the methods, by which so many of the laws of the physical world have been numbered among truths irrevocably acquired and universally assented to, can be made instrumental to the gradual formation of a similar body of received doctrine in moral and political science.

Kafka often describes himself as a bloodless figure: a human being who doesn't really participate in the life of his fellow human beings, someone who doesn't actually live in the true sense of the word, but who consists rather of words and literature. In my view, that is, however, only half true. In a roundabout way through literature, which presupposes empathy and exact observation, he immerses himself again in the life of society; in a certain sense he comes back to it.

By establishing a social policy that keeps physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia illegal but recognizes exceptions, we would adopt the correct moral view: the onus of proving that everything had been tried and that the motivation and rationale were convincing would rest on those who wanted to end a life.

It is paltry philosophy if in the old-fashioned way one lays down rules and principles in total disregard of moral values . As soon as these appear one regards them as exceptions, which gives them a certain scientific status, and thus makes them into rules. Or again one may appeal to genius , which is above all rules; which amounts to admitting that rules are not only made for idiots , but are idiotic in themselves.