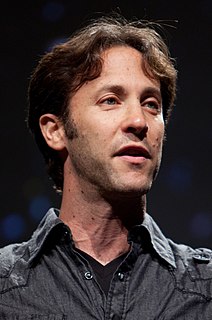

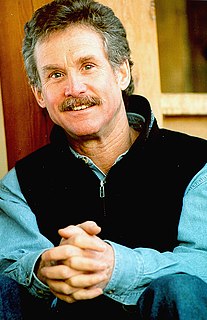

A Quote by David Eagleman

Scientists often talk of parsimony (as in "the simplest explanation is probably correct," also known as Occam's razor), but we should not get seduced by the apparent elegance of argument from parsimony; this line of reasoning has failed in the past at least as many times as it has succeeded.

Related Quotes

And this shows that people want to be stupid and they do not want to know the truth. And it shows that something called Occam's razor is true. And Occam's razor is not a razor that men shave with but a Law, and it says: Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem. Which is Latin and it means: No more things should be presumed to exist than are absolutely necessary. Which means that a murder victim is usually killed by someone known to them and fairies are made out of paper and you can't talk to someone who is dead.

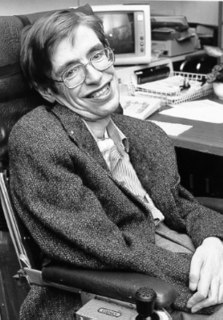

It is more parsimonious to assume that the sun goes around the Earth, that atoms at the smallest scale operate in accordance with the same rules that objects at larger scales follow, and that we perceive what is really out there. All of these positions were long defended by argument from parsimony, and they were all wrong.

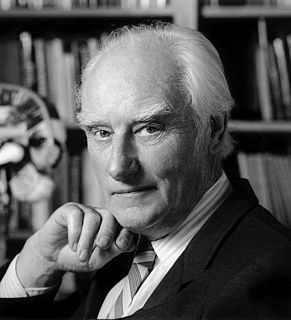

[Theory is] an explanation that has been confirmed to such a degree, by observation and experiment, that knowledgeable experts accept it as fact. That's what scientists mean when they talk about a theory: not a dreamy and unreliable speculation, but an explanatory statement that fits the evidence. They embrace such an explanation confidently but provisionally - taking it as their best available view of reality, at least unil some severely conflicting data or some better explanation might come along.

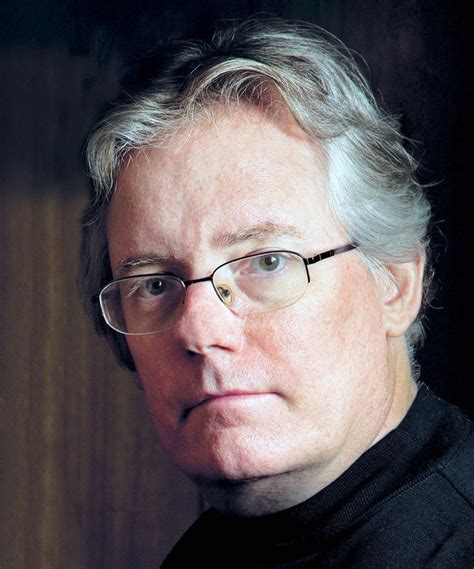

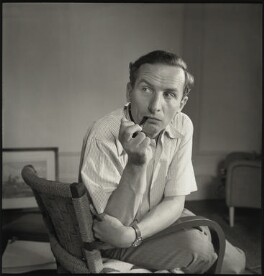

It really comes down to parsimony, economy of explanation. It is possible that your car engine is driven by psychokinetic energy, but if it looks like a petrol engine, smells like a petrol engine and performs exactly as well as a petrol engine, the sensible working hypothesis is that it is a petrol engine.

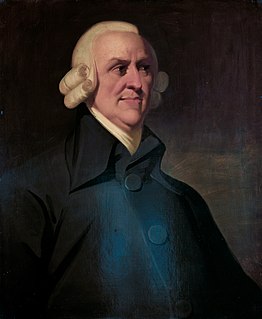

Capitals are increased by parsimony, and diminished by prodigalityand misconduct. By what a frugal man annually saves he not onlyaffords maintenance to an additional number of productive hands?but?he establishes as it were a perpetual fund for the maintenance of an equal number in all times to come.