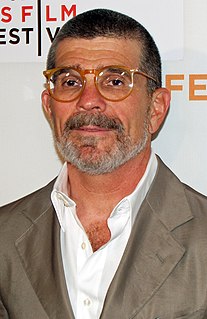

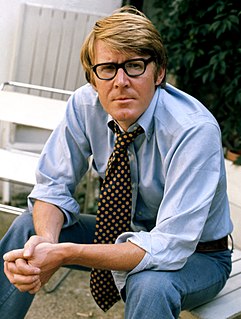

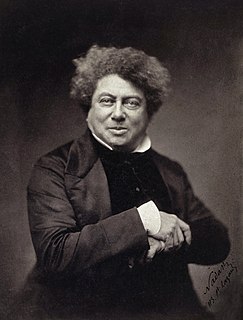

A Quote by David Mamet

Forget narrative, backstory, characterisation, exposition, all of that. Just make the audience want to know what happens next.

Related Quotes

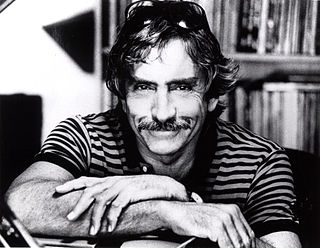

Consider: for all the gobbledegook [film studio] executives spout about backstory, all that we, the audience, want to know is what happens next. That's the only thing that's going on. . . . Character is nothing other than action, and character-driven means The plot stinks, and you'd better hope the star is popular enough to open the movie in spite of it.

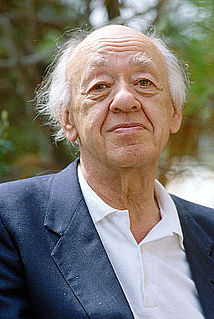

One of the tricks is to have the exposition conveyed in a scene of conflict, so that a character is forced to say things you want the audience to know - as, for example, if he is defending himself against somebody's attack, his words of defense seem Justified even though his words are actually expository words. Something appears to be happening, so the audience believes it is witnessing a scene (which it is), not listening to expository speeches. Humor is another way of getting exposition across.

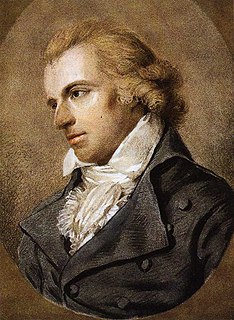

You hear it said time and time again by successful directors: You have to make a movie for yourself. Don't make it for anyone else. My style of filmmaking happens to be give the audience what they know they don't want, but they want. Ultimately I have to write and direct in a way that let's just say, you don't want to regret making a choice.