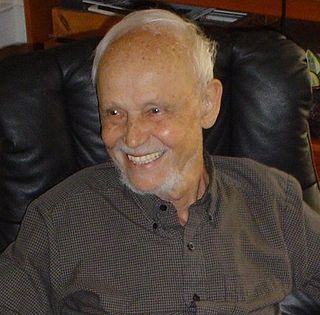

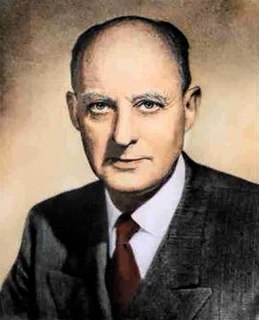

A Quote by David Novak

The rabbi is often the regular preacher in the synagogue, the man whose sermons offer his community more general theological and moral guidance.

Related Quotes

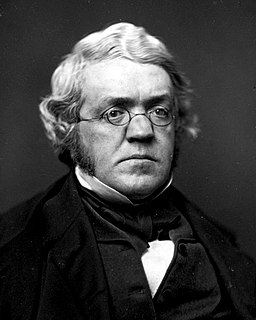

Henry Ward Beecher, so the story goes, was once asked by a young preacher how he could keep his congregation wide awake and attentive during his sermons. Beecher replied that he always had a man watch for sleepers, with instructions, as soon as he saw anyone start nodding or dozing, to hasten to the pulpit and wake up the preacher. Aren't you and I usually less sensible? Would we not be inclined to have the watcher wake up not ourselves but the fellows caught sleeping? In other words, aren't we disposed always to blame others?

The man whose little sermon is ‘repent’ sets himself against his age, and will for the time being be battered mercilessly by the age whose moral tone he challenges. There is but one end for such a man—‘off with his head!’ You had better not try to preach repentance until you have pledged your head to heaven

The life-giving preacher is a man of God, whose heart is ever athirst for God, whose soul is ever following hard after God, whose eye is single to God, and in whom by the power of God's Spirit the flesh and the world have been crucified, and his ministry is like the generous flood of a life-giving river.

I am willing to allow that smoking is a moral weakness, but on the other hand, we must beware of the man without weaknesses. He is not to be trusted. He is apt to be always sober and he cannot make a single mistake. His habits are likely to be regular, his existence more mechanical and his head always maintains its supremacy over his heart. Much as I like reasonable persons, I hate completely rational beings.

There is a certain sort of man whose doom in the world is disappointment, who excels in it, and whose luckless triumphs in his meek career of life, I have often thought, must be regarded by the kind eyes above with as much favor as the splendid successes and achievements of coarser and more prosperous men.

For God to be kept out of the classroom or out of America's public debate by nervous school administrators or overcautious politicians serves no one's interests. That restriction prevents people from drawing on this country's rich and diverse religious heritage for guidance, and it degrades the nation's moral discourse by placing a whole realm of theological reasoning out of bounds. The price of that sort of quarantine, at a time of moral dislocation, is - and has been - far too high.

The Talmud tells a story about a great Rabbi who is dying, he has become a goses, but he cannot die because outside all his students are praying for him to live and this is distracting to his soul. His maidservant climbs to the roof of the hut where the Rabbi is dying and hurls a clay vessel to the ground. The sound diverts the students, who stop praying. In that moment, the Rabbi dies and his soul goes to heaven. The servant, too, the Talmud says, is guaranteed her place in the world to come.

The man who has given himself to his country loves it better; the man who has fought for his friend honors him more; the man who has labored for his community values more highly the interests he has sought to conserve; the man who has wrought and planned and endured for the accomplishment of God's plan in the world sees the greatness of it, the divinity and glory of it, and is himself more perfectly assimilated to it.

Certainly I had from an early age a sense of the power and beauty of religious texts - the awesome magnitude of the Bible stories I was reading as a child. The hymns. The sermons. I can still vividly hear the sermons and the pieces of soft piano music played after them, the preacher asking if anyone wanted to come up to the altar and accept Christ as their savior.