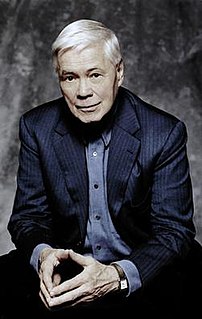

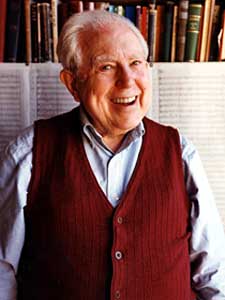

A Quote by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Brahms believed that there was no need to publish absolutely everything that Schubert ever wrote.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

...stories about [the German composer Johannes] Brahms's rudeness and wit amused me in particular. For instance, I loved the one about how a great wine connoisseur invited the composer to dinner. 'This is the Brahms of my cellar,' he said to his guests, producing a dust-covered bottle and pouring some into the master's glass. Brahms looked first at the color of the wine, then sniffed its bouquet, finally took a sip, and put the glass down without saying a word. 'Don't you like it?' asked the host. 'Hmm,' Brahms muttered. 'Better bring your Beethoven!'

the writer must resist this temptation [to quote] and do his best with his own tools. It would be most convenient for us musicians if, arrived at a given emotional crisis in our work, we could simply stick in a few bars of Brahms or Schubert. Indeed many composers have no hesitation in so doing. But I have never heard the practice defended; possibly because that hideous symbol of petty larceny, the inverted comma, cannot well be worked into a musical score.