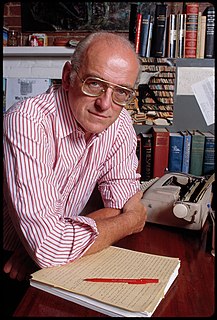

A Quote by Donald E. Westlake

I was writing everything. I grew up in Albany, New York, and I was never any farther west than Syracuse, and I wrote Westerns. I wrote tiny little slices of life, sent them off to The Sewanee Review, and they always sent them back. For the first 10 years I was published, I'd say, "I'm a writer disguised as a mystery writer." But then I look back, and well, maybe I'm a mystery writer. You tend to go where you're liked, so when the mysteries were being published, I did more of them.

Related Quotes

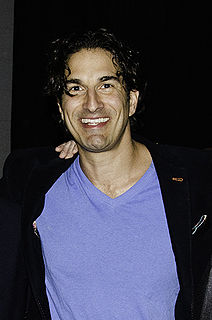

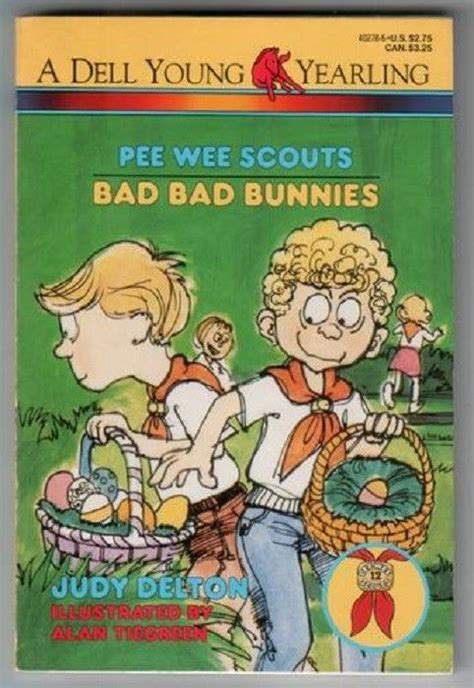

I was writing at a really young age, but it took me a long time to be brave enough to become a published writer, or to try to become a published writer. It's a very public way to fail. And I was kind of scared, so I started out as a ghost writer, and I wrote for other series, like Disney 'Aladdin' and 'Sweet Valley' and books like that.

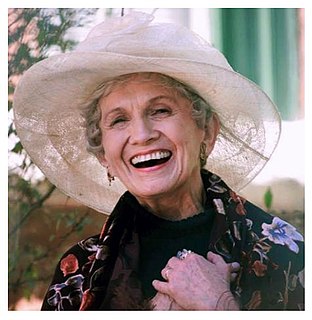

'Royal Beatings' was my first story, and it was published in 1977. But I sent all my early stories to 'The New Yorker' in the 1950s, and then I stopped sending for a long time and sent only to magazines in Canada. 'The New Yorker' sent me nice notes, though - penciled, informal messages. They never signed them. They weren't terribly encouraging.

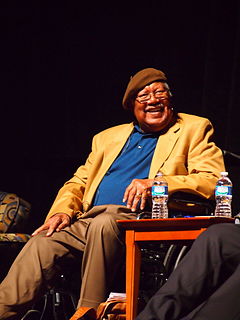

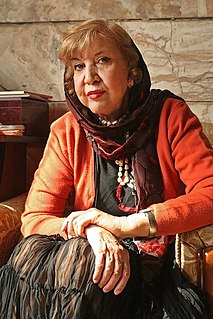

The nightmare of censorship has always cast a shadow over my thoughts. Both under the previous state and under the Islamic state, I have said again and again that, when there is an apparatus for censorship that filters all writing, an apparatus comes into being in every writer's mind that says: "Don't write this, they won't allow it to be published." But the true writer must ignore these murmurings. The true writer must write. In the end, it will be published one day, on the condition that the writer writes the truth and does not dissemble.

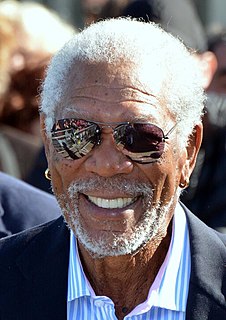

I have a problem with writer/directors, personal. I can't work well with both of them on the set, if both of them are giving instructions. Writers tend to be in love with what they wrote. You can't always translate the words into the meaning, sometimes the meaning is better served without the words, difficult to make a writer to try to understand that. It gets, sometimes, tense.