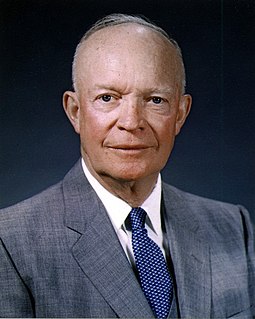

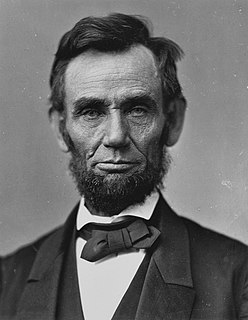

A Quote by Dwight D. Eisenhower

We have never stopped sin by passing laws; and in the same way, we are not going to take a great moral ideal and achieve it merely by law.

Related Quotes

Blind obedience is itself an abuse of human morality. It is a misuse of the human soul in the name of religious commitment. It is a sin against individual conscience. It makes moral children of the adults from whom moral agency is required. It makes a vow, which is meant to require religious figures to listen always to the law of God, beholden first to the laws of very human organizations in the person of very human authorities. It is a law that isn't even working in the military and can never substitute for personal morality.

In war, in some sense, lies the very genius of law. It is law creative and active; it is the first principle of the law. What is human warfare but just this, - an effort to make the laws of God and nature take sides with one party. Men make an arbitrary code, and, because it is not right, they try to make it prevail by might. The moral law does not want any champion. Its asserters do not go to war. It was never infringed with impunity. It is inconsistent to decry war and maintain law, for if there were no need of war there would be no need of law.

It is an occult law moreover, that no man can rise superior to his individual failings without lifting, be it ever so little, the whole body of which he is an integral part. In the same way no one can sin, nor suffer the effects of sin, alone. In reality, there is no such thing as 'separateness' and the nearest approach to that selfish state which the laws of life permit is in the intent or motive.

No society can exist if respect for the law does not to some extent prevail; but the surest way to have the laws respected is to make them respectable. When law and morality are in contradiction, the citizen finds himself in the cruel dilemma of either losing his moral sense or of losing respect for the law, two evils of which one is as great as the other, and between which it is difficult to choose.

Nothing can better express the feelings of the scientist towards the great unity of the laws of nature than in Immanuel Kant's words: "Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing awe: the stars above me and the moral law within me."... Would he, who did not yet know of the evolution of the world of organisms, be shocked that we consider the moral law within us not as something given, a priori, but as something which has arisen by natural evolution, just like the laws of the heavens?

It is indeed a singular thing that people wish to pass laws to nullify the disagreeable consequences that the law of responsibility entails. Will they never realize that they do not eliminate these consequences but merely pass them along to other people? The result is one injustice the more and one moral the less.

The Law was given by Moses; the moral law, to discover the extent and abounding sin; the ceremonial law, to point out, by typical sacrifices and ablutions, the way in which forgiveness was to be sought and obtained. But grace, to relieve us from the condemnation of the one, and truth answerable to the types and shadows of the other, came by Jesus Christ.

When you say there's too much evil in this world you assume there's good. When you assume there's good, you assume there's such a thing as a moral law on the basis of which to differentiate between good and evil. But if you assume a moral law, you must posit a moral Law Giver, but that's Who you're trying to disprove and not prove. Because if there's no moral Law Giver, there's no moral law. If there's no moral law, there's no good. If there's no good, there's no evil. What is your question?