A Quote by E. M. Forster

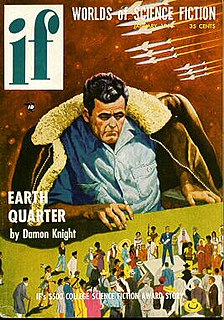

Our easiest approach to a definition of any aspect of fiction is always by considering the sort of demand it makes on the reader. Curiosity for the story, human feelings and a sense of value for the characters, intelligence and memory for the plot. What does fantasy ask of us? It asks us to pay something extra.

Related Quotes

The most difficult part of writing a book is not devising a plot which will captivate the reader. It's not developing characters the reader will have strong feelings for or against. It is not finding a setting which will take the reader to a place he or she as never been. It is not the research, whether in fiction or non-fiction. The most difficult task facing a writer is to find the voice in which to tell the story.

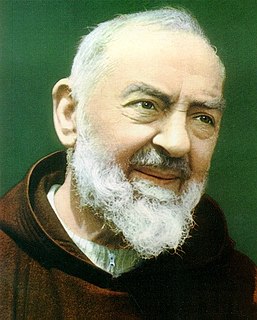

Our Lord’s making of a disciple is supernatural. He does not build on any natural capacity of ours at all. God does not ask us to do the things that are naturally easy for us- He only asks us to do the things that we are perfectly fit to do through His grace, and that is where the cross we must bear will always come.

Good writing is good writing. In many ways, it’s the audience and their expectations that define a genre. A reader of literary fiction expects the writing to illuminate the human condition, some aspect of our world and our role in it. A reader of genre fiction likes that, too, as long as it doesn’t get in the way of the story.

If we wish to know about a man, we ask 'what is his story--his real, inmost story?'--for each of us is a biography, a story. Each of us is a singular narrative, which is constructed, continually, unconsciously, by, through, and in us--through our perceptions, our feelings, our thoughts, our actions; and, not least, our discourse, our spoken narrations. Biologically, physiologically, we are not so different from each other; historically, as narratives--we are each of us unique.

Curiosity and irreverence go together. Curiosity cannot exist without the other. Curiosity asks, "Is this true?" "Just because this has always been the way, is the best or right way of life, the best or right religion, political or economic value, morality?" To the questioner, nothing is sacred. He detests dogma, defies any finite definition of morality, rebels against any repression of a free, open search of ideas no matter where they may lead. He is challenging, insulting, agitating, discrediting. He stirs unrest.

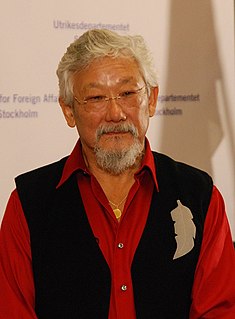

My deeply held belief is that if a god of anything like the traditional sort exists, our curiosity and intelligence are provided by such a god. We would be unappreciative of those gifts (as well as unable to take such a course of action) if we suppressed our passion to explore the universe and ourselves. On the other hand, if such a traditional god does not exist, our curiosity and our intelligence are the essential tools for managing our survival. In either case, the enterprise of knowledge is consistent with both science and religion, and is essential for the welfare of the human species.

Something similar happens on the other side of the equation: Giving kindness does us as much good as receiving it. . . . The true benefit of kindness is being kind. Perhaps more than any other factor, kindness gives meaning and value to our life, raises us above our troubles and our battles, and makes us feel good about ourselves.

The institutions of human society treat us as parts of a machine. They assign us ranks and place considerable pressure upon us to fulfill defined roles. We need something to help us restore our lost and distorted humanity. Each of us has feelings that have been suppressed and have built up inside. There is a voiceless cry resting in the depths of our souls, waiting for expression. Art gives the soul's feelings voice and form.

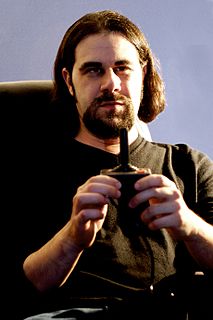

Our ideas of happiness, gratification, contentment, satisfaction, all demand that those feelings come from within us. If you flip that on its head and say "What if I took the world at face value?" and then ask "What can I do with what is given?" it's an interesting trick to turn around the whole problem of how you feel.