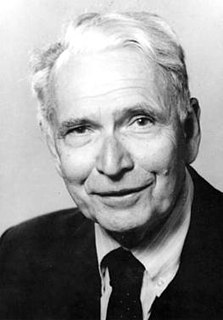

A Quote by E. O. Wilson

The second half of the 20th century was a golden age of molecular biology, and it was one of the golden ages of the history of science. Molecular biology was so successful and made such a powerful alliance with the medical scientists that the two together just flourished. And they continue to flourish.

Related Quotes

The students of biodiversity, the ones we most need in science today, have an enormous task ahead of molecular biology and the medical scientists. Studying model species is a great idea, but we need to combine that with biodiversity studies and have those properly supported because of the contribution they can make to conservation biology, to agrobiology, to the attainment of a sustainable world.

If belief in evolution is a requirement to be a real scientist, it’s interesting to consider a quote from Dr. Marc Kirschner, founding chair of the Department of Systems Biology at Harvard Medical School:

“In fact, over the last 100 years, almost all of biology has proceeded independent of evolution, except evolutionary biology itself. Molecular biology, biochemistry, physiology, have not taken evolution into account at all.

It is now widely realized that nearly all the 'classical' problems of molecular biology have either been solved or will be solved in the next decade. The entry of large numbers of American and other biochemists into the field will ensure that all the chemical details of replication and transcription will be elucidated. Because of this, I have long felt that the future of molecular biology lies in the extension of research to other fields of biology, notably development and the nervous system.

The idea would be in my mind - and I know it sounds strange - is that the most important advances in medicine would be made not by new knowledge in molecular biology, because that's exceeding what we can even use. It'll be made by mathematicians, physicists, computer scientists, figuring out a way to get all that information together.

A paradigm shift is the best a scientist can hope for. Whenever I smell an opportunity like that, I go after it. You have a new discovery that something's working in a different way than you thought. And this is particularly true in molecular and cell biology, which is structural biology and has the least potential for controversy and partisanship among the biological scientists. You're dealing with a concrete object that's either there or not there.