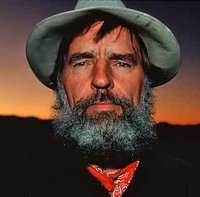

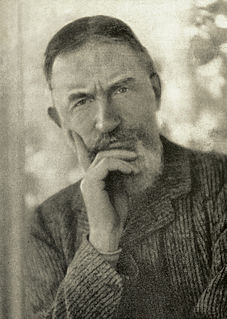

A Quote by Edward Abbey

There comes a point, in literary objectivity, when the author's self- effacement is hard to distinguish from moral cowardice.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

Because every book of art, be it a poem or a cupola, is understandably a self-portrait of its author, we won't strain ourselves too hard trying to distinguish between the author's persona and the poem's lyrical hero. As a rule, such distinctions are quite meaningless, if only because a lyrical hero is invariably an author's self-projection.

By "moral discipline," I mean self-discipline based on moral standards. Moral discipline is the consistent exercise of agency to choose the right because it is right, even when it is hard. It rejects the self-absorbed life in favor of developing character worthy of respect and true greatness through Christlike service.

Humility is just as much the opposite of self-abasement as it is of self-exaltation. To be humble is not to make comparisons. Secure in its reality, the self is neither better nor worse, bigger nor smaller, than anything else in the universe. It is ? is nothing, yet at the same time one with everything. It is in this sense that humility is absolute self-effacement.

Many journalists become very defensive when you suggest to them that they are anything but impartial and objective. The problem with those words "impartiality" and "objectivity" is that they have lost their dictionary meaning. They've been taken over. "Impartiality" and "objectivity" now mean the establishment point of view.