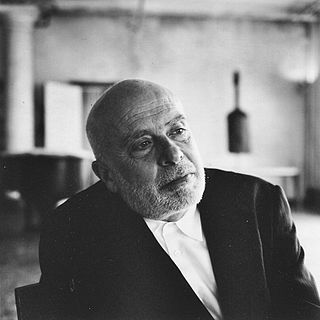

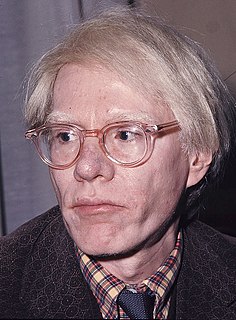

A Quote by Edward Ruscha

Yes, there's a certain power to a photograph. The camera has a way of disorienting a person, if it wants to and, for me, when it disorients, it's got real value.

Related Quotes

Film, television, and working with a camera is such an intimate art form that if a camera is right on you, and I've got your face filling the screen, you have to be real. If you do anything that is fake, you're not going to get away with it, because the camera is right there, and the story is being told in a very real way.

For the photograph's immobility is somehow the result of a perverse confusion between two concepts: the Real and the Live: by attesting that the object has been real, the photograph surreptitiously induces belief that it is alive, because of that delusion which makes us attribute to Reality an absolute superior, somehow eternal value; but by shifting this reality to the past ("this-has-been"), the photograph suggests that it is already dead.

If you look at a photograph, and you think, 'My isn't that a beautiful photograph,' and you go on to the next one, or 'Isn't that nice light?' so what? I mean what does it do to you or what's the real value in the long run? What do you walk away from it with? I mean, I'd much rather show you a photograph that makes demands on you, that you might become involved in on your own terms or be perplexed by.

... I'm sort of a nervous person with the camera, so I will just shoot arbitrarily until I can focus and compose something, and then I make a shot. So generally, in [the] proof sheets, there are only three or four really concentrated efforts to take a photograph. It's not like a professional kind of person who sets it up so every photograph looks really cool.

I think that the exactitude of the photograph has a sort of compelling nature based in its power to duplicate life. But to me the real power of photography is based in death: the fact that somehow it can enliven that which is not there in a kind of stultifying frightened way, because it seems to me that part of one's life is made up of a constant confrontation with one's own death.

Of course, the camera is a far more objective and trustworthy witness than a human being. We know that a Brueghel or Goya or James Ensor can have visions or hallucinations, but it is generally admitted that a camera can photograph only what is actually there, standing in the real world before its lens.