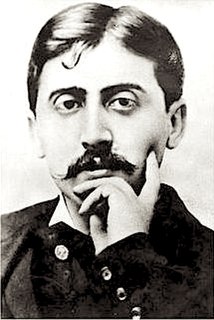

A Quote by Elif Batuman

Tolstoy didn't know about steampunk or cyborgs, but he did know about the nightmarishness of steam power, unruly machines, and the creepy half-human status of the Russian peasant classes. In 'Anna Karenina,' nineteenth-century life itself is a relentless, relentlessly modern machine, flattening those who oppose it.

Related Quotes

One of the things that really impressed me about Anna Karenina when I first read it was how Tolstoy sets you up to expect certain things to happen - and they don't. Everything is set up for you to think Anna is going to die in childbirth. She dreams it's going to happen, the doctor, Vronsky and Karenin think it's going to happen, and it's what should happen to an adulteress by the rules of a nineteenth-century novel. But then it doesn't happen. It's so fascinating to be left in that space, in a kind of free fall, where you have no idea what's going to happen.

In high school I read [Lev] Tolstoy's "Anna Karenina" and loved it. Then I read [Friedrich] Nietzsche's "On the Genealogy of Morals" and that hit me hard. I don't know where I got it. My parents warned me not to mention either of those books when I went for my college interviews so I wouldn't seem like an egghead. They told me to talk about sports.

Evil itself may be relentless. I will grant you that, but love is relentless too. Friendship is a relentless force. Family is a relentless force. Faith is relentless force. The human spirit is relentless, and the human heart outlasts - and can defeat - even the most relentless force of all, which is time.

Gordie, the white boy genius, gave me this book by a Russian dude named Tolstoy, who wrote, 'Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.' Well, I hate to argue with a Russian genius, but Tolstoy didn't know Indians, and he didn't know that all Indian families are unhappy for the same exact reasons: the frikkin' booze.

In a vacuum all photons travel at the same speed. They slow down when travelling through air or water or glass. Photons of different energies are slowed down at different rates. If Tolstoy had known this, would he have recognised the terrible untruth at the beginning of Anna Karenina? 'All happy families are alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own particular way.' In fact it's the other way around. Happiness is a specific. Misery is a generalisation. People usually know exactly why they are happy. They very rarely know why they are miserable.

I think if I were reading to a grandchild, I might read Tolstoy's War and Peace. They would learn about Russia, they would learn about history, they would learn about human nature. They would learn about, "Can the individual make a difference or is it great forces?" Tolstoy is always battling with those large issues. Mostly, a whole world would come alive for them through that book.

It was only in the late nineteenth century and then the twentieth century, with the maturation of consumer capitalism, that a shift was made toward the cultivation of unbounded desire. We must appreciate this to realize that late modern consumption, consumption as we now know it, is not fundamentally about materialism or the consumption of physical goods. Affluence and consumer-oriented capitalism have moved us well beyond the undeniable efficiencies and benefits of refrigeration and indoor plumbing.