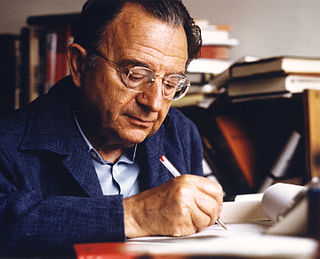

A Quote by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

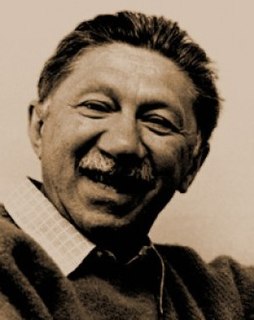

I was destined to work with dying patients. I had no choice when I encountered my first AIDS patient. I felt called to travel some 250,000 miles each year to hold workshops that helped people cope with the most painful aspects of life, death and the transition between the two.

Related Quotes

We are all so bent and determined to get what we want, we miss the lessons that could be learned from life's experiences. Many of my AIDS patients discovered that the last year of their lives was by far their best. Many have said they wouldn't have traded the rich quality of that last year of life for a healthier body. Sadly, it is only when tragedy strikes that most of us begin attending to the deeper aspects of life. It is only then that we attempt to go beyond surface concerns-what we look like, how much money we make, and so forth-to discover what's really important.

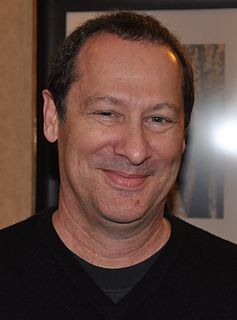

My first car was, as depicted in 'Sleepwalk with Me,' my mother's '92 Volvo station wagon that had 80,000 miles on it, and I had put 40,000 miles on it, so by the time it retired it had 120,000, and I basically killed it. It served me well, and my mechanic was always very angry with me because I just didn't properly care for it.

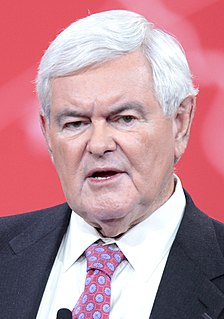

Malmo, with its 280,000 residents, is Sweden's third-largest city. To see a physician, a patient must go to one of two local clinics before they can see a specialist. The clinics have security guards to keep patients from getting unruly as they wait hours to see a doctor. The guards also prevent new patients from entering the clinic when the waiting room is considered full. Uppsala, a city with 200,000 people, has only one specialist in mammography. Sweden's National Cancer Foundation reports that in a few years most Swedish women will not have access to mammography.

We economists, in our classes, teach students that to some degree, price discrimination is actually a good thing; that it allows you to serve lower-income people. Take Africa, with AIDS. They could never finance what an AIDS cocktail costs here, over $10,000 a year. But if you sold it to them for $300 a year, which just barely covers cost, they could probably serve quite a few of their citizens, with World Bank help. We economists say that will be beneficial. But it's a two-tier system; yes, African people pay less than we would pay.

Now I'm not going to go, "Oh my God, what are people saying about me?" I had a choice to be a student and not become a model, and becoming a doctor was another one of my dreams. I had a choice between not becoming a singer or becoming a songwriter and writing behind the scenes; nobody would have seen me writing songs for other people. I had the choice of not marrying my man; we could have just been hidden lovers, but I couldn't cope with it. I had these choices to do all these things, so I'm not going to cry over a life which has been really lucky.

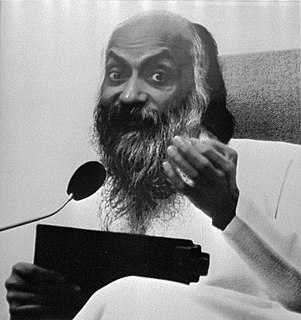

When one existentially awakens from within, the relation of birth-and-death is not seen as a sequential change from the former to the latter. Rather, living as it is, is no more than dying, and at the same time there is no living separate from dying. This means that life itself is death and death itself is life. That is, we do not shift sequentially from birth to death, but undergo living-dying in each and every moment.

Birth leads to death, death precedes birth. So if you want to see life as it really is, it is rounded on both the sides by death. Death is the beginning and death is again the end, and life is just the illusion in between. You feel alive between two deaths; the passage joining one death to another you call life. Buddha says this is not life. This life is dukkha - misery. This life is death.