A Quote by Elizabeth Gaskell

Mr Thornton would rather have heard that she was suffering the natural sorrow. In the first place, there was selfishness enough in him to have taken pleasure in the idea that his great love might come in to comfort and console her; much the same kind of strange passionate pleasure which comes stinging through a mother's heart, when her drooping infant nestles close to her, and is dependent upon her for everything.

Related Quotes

The good enough mother, owing to her deep empathy with her infant, reflects in her face his feelings; this is why he sees himselfin her face as if in a mirror and finds himself as he sees himself in her. The not good enough mother fails to reflect the infant's feelings in her face because she is too preoccupied with her own concerns, such as her worries over whether she is doing right by her child, her anxiety that she might fail him.

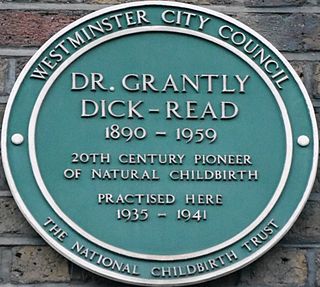

It is as great a crime to leave a woman alone in her agony and deny her relief from her suffering as it is to insist upon dulling the consciousness of a natural mother who desires above all things to be aware of the final reward of her efforts, whose ambition is to be present, in full possession of her senses, when the infant she already adores greets her with its first loud cry and the soft touch of its restless body upon her limbs.

She sat leaning back in her chair, looking ahead, knowing that he was as aware of her as she was of him. She found pleasure in the special self-consciousness it gave her. When she crossed her legs, when she leaned on her arm against the window sill, when she brushed her hair off her forehead - every movement of her body was underscored by a feeling the unadmitted words for which were: Is he seeing it?

She wondered whether there would ever come an hour in her life when she didn't think of him -- didn't speak to him in her head, didn't relive every moment they'd been together, didn't long for his voice and his hands and his love. She had never dreamed of what it would feel like to love someone so much; of all the things that had astonished her in her adventures, that was what astonished her the most. She thought the tenderness it left in her heart was like a bruise that would never go away, but she would cherish it forever.

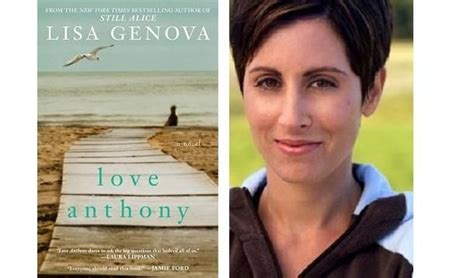

But will I always love her? Does my love for her reside in my head or my heart? The scientist in her believed that emotion resulted from complex limbic brain circuitry that was for her, at this very moment, trapped in the trenches of a battle in which there would be no survivors. The mother in her believed that the love she hadd for her daughter was safe from the mayhem in her mind, because it lived in her heart.

Little Lotte thought of everything and nothing. Her hair was as golden as the sun's rays, and her soul as clear and blue as her eyes. She wheedled her mother, was kind to her doll, took great care of her frock and her red shoes and her fiddle, but loved most of all, when she went to sleep, to hear the Angel of Music.

When she liked anyone it was quite natural for her to go to bed with him. She never thought twice about it. It was not vice; it wasn't lasciviousness; it was her nature. She gave herself as naturally as the sun gives heat or the flowers their perfume. It was a pleasure to her and she liked to give pleasure to others.

I had always been scrupulously careful to avoid the smallest suggestion of infant indoctrination, which I think is ultimately responsible for much of the evil in the world. Others, less close to her, showed no such scruples, which upset me, as I very much wanted her, as I want all children, to make up her own mind freely when she became old enough to do so. I would encourage her to think, without telling her what to think.

Mother is in herself a concrete denial of the idea of sexual pleasure since her sexuality has been placed at the service of reproductive function alone. She is the perpetually violated passive principle; her autonomy has been sufficiently eroded by the presence within her of the embryo she brought to term. Her unthinking ability to reproduce, which is her pride, is, since it is beyond choice, not a specific virtue of her own.

Her [Eleanor Roosevelt] father was the love of her life. Her father always made her feel wanted, made her feel loved, where her mother made her feel, you know, unloved, judged harshly, never up to par. And she was her father's favorite, and her mother's unfavorite. So her father was the man that she went to for comfort in her imaginings.

Neither loss of father, nor loss of mother, dear as she was to Mr Thornton, could have poisoned the remembrance of the weeks, the days, the hours, when a walk of two miles, every step of which was pleasant, as it brought him nearer and nearer to her, took him to her sweet presence - every step of which was rich, as each recurring moment that bore him away from her made him recal some fresh grace in her demeanour, or pleasant pungency in her character.

Bedding her could be anything from tenderness to riot, but to take her when she was a bit the worse for drink was always a particular delight. Intoxicated, she took less care for him than usual; abandoned and oblivious to all but her own pleasure, she would rake him, bite him - and beg him to serve her so, as well. He loved the feeling of power in it, the tantalizing choice between joining her at once in animal lust, or of holding himself-for a time- in check, so as to drive her at his whim.

He lifted his gaze to the framed photograph of Tanya and him taken on their wedding day. God, she had been lovely. Her smile had come through her eyes straight from her heart. He had known unequivocally that she loved him. He believed to this day that she had died knowing that he loved her. How could she not know? He had dedicated his life to never letting her doubt it.

Now, Bella suspected by this time that Mr. Rokesmith admired her. Whether the knowledge (for it was rather that than suspicion) caused her to incline to him a little more, or a little less, than she had done at first; whether it rendered her eager to find out more about him, because she sought to establish reason for her distrust, or because she sought to free him from it; was as yet dark to her own heart. But at most times he occupied a great amount of her attention.