A Quote by Erasmus Darwin

The great CREATOR of all things has infinitely diversified the works of his hands, but has at the same time stamped a certain similitude on the features of nature, that demonstrates to us, that the whole is one family of one parent.

Related Quotes

It is natural to men to judge of things less known, by some similitude they observe, or think they observe, between them and things more familiar or better known. In many cases, we have no better way of judging. And, where the things compared have really a great similitude in their nature, when there is reason to think that they are subject to the same laws, there may be a considerable degree of probability in conclusions drawn from analogy.

Da Vinci was as great a mechanic and inventor as were Newton and his friends. Yet a glance at his notebooks shows us that what fascinated him about nature was its variety, its infinite adaptability, the fitness and the individuality of all its parts. By contrast what made astronomy a pleasure to Newton was its unity, its singleness, its model of a nature in which the diversified parts were mere disguises for the same blank atoms.

This writer, who is horribly perspicacious and vigorous, demonstrates the certainty of a great European war, and regards it with the peculiar satisfaction excited by such things in a certain order of mind. His phrases about "dire calamity" and so on mean nothing; the whole tenor of his writing proves that he represents, and consciously, one of the forces which go to bring war about; his part in the business is a fluent irresponsibility, which casts scorn on all who reluct at the "inevitable." Persistent prophecy is a familiar way of assuring the event.

It is not therefore the business of philosophy, in our present situation in the universe, to attempt to take in at once, in one view, the whole scheme of nature; but to extend, with great care and circumspection, our knowledge, by just steps, from sensible things, as far as our observations or reasonings from them will carry us, in our enquiries concerning either the greater motions and operations of nature, or her more subtile and hidden works. In this way Sir Isaac Newton proceeded in his discoveries.

Souls never die, but always on quitting one abode pass to another. All things change, nothing perishes. The soul passes hither and thither, occupying now this body, now that... As a wax is stamped with certain figures, then melted, then stamped anew with others, yet it is always the same wax. So, the Soul being always the same, yet wears at different times different forms.

Man wants to see nature and evolution as separate from human activities. There is a natural world, and there is man. But man also belongs to the natural world. If he is a ferocious predator, that too is part of evolution. If cod and haddock and other species cannot survive because man kills them, something more adaptable will take their place. Nature, the ultimate pragmatist, doggedly searches for something that works. But as the cockroach demonstrates, what works best in nature does not always appeal to us.

The folly of men has enhanced the value of gold and silver because of their scarcity; whereas, on the contrary, it is their opinion that Nature, as an indulgent parent, has freely given us all the best things in great abundance, such as water and earth, but has laid up and hid from us the things that are vain and useless.

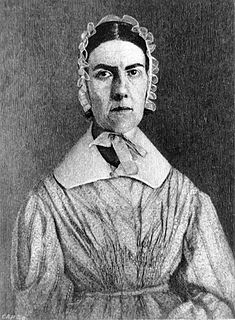

Human beings have rights, because they are moral beings: the rights of all men grow out of their moral nature; and as all men havethe same moral nature, they have essentially the same rights. These rights may be wrested from the slave, but they cannot be alienated: his title to himself is as perfect now, as is that of Lyman Beecher: it is stamped on his moral being, and is, like it, imperishable.

The beauty of man's being, fashioned as he is in the fairest of forms, demonstrates the existence of the Maker, while at the same time the fact that, together with his comprehensive abilities, lodged in that fairest of forms, he soon declines and dies, demonstrates the existence of the resurrection.

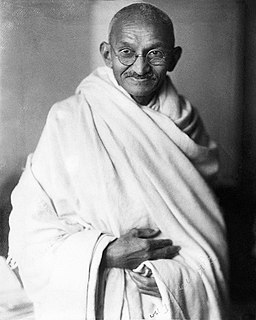

It is a tragedy of the first magnitude that millions of people have ceased to use their hands as hands. Nature has bestowed upon us this great gift which is our hands. If the craze for machinery method continues, it is highly likely that a time will come when we shall be so incapacitated and weak that we shall begin to curse ourselves for having forgotten the use of the living machines given to us by God.

After sketching his program for the scientific revolution that he foresaw, Bacon ends his account with a prayer: "Humbly we pray that this mind may be steadfast in us, and that through these our hands, and the hands of others to whom thou shalt give the same spirit, thou wilt vouchsafe to endow the human family with new mercies". That is still a good prayer for all of us as we begin the twenty-first century.