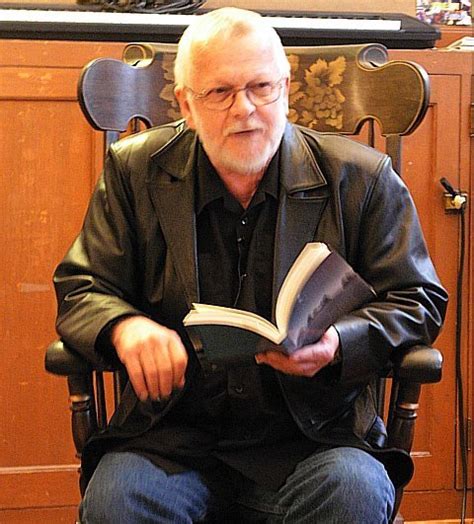

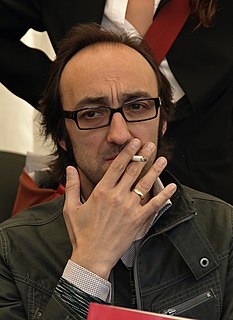

A Quote by Etgar Keret

When my books were translated, it was always about the characters, because the unique language aspect was lost in translation.

Related Quotes

I've never translated more than one book by any author. But I'm fascinated by translators who have, like Richard Zenith, who's translated so much of Fernando Pessoa's work. I get restless for a new kind of influence. The books I've translated are books I want to learn from as a writer, to be intoxicated by. And translation is an act of writing in itself. It's an act of recreation - of a writer's cadence and tone and everything that distinguishes the voice in the book.

I don't speak any languages well enough to make an expert assessment on writing in translation, but since I'm interested in awkwardness in prose, I find I like the way translated texts can sometimes acquire awkwardness in the process of translation. There's a discordance translation can create which I think is sometimes seen as a weakness but which I think can be a really interesting aspect of the text.

In fact, many of the quotes in my books are quotes which were translated from English and that I read already translated into Spanish. I'm not really concerned with what the original version in English was, because the important thing for me is that I received them already translated, and they've influenced my original worldview as translations, not as original quotations.

If a novel is written in a certain language with certain characters from a particular community and the story is very good or illuminating, then that work is translated into the language of another community - then they begin to see through their language that the problems described there are the same as the problems they are having. They can identify with characters from another language group.

Poetry cannot be translated; and, therefore, it is the poets that preserve the languages; for we would not be at the trouble to learn a language if we could have all that is written in it just as well in a translation. But as the beauties of poetry cannot be preserved in any language except that in which it was originally written, we learn the language.

In translation studies we talk about domestication - translation styles that make something familiar - or estrangement - translation styles that make something radically different. I use a lot of both in my translation, and modernism does both. For instance, if you look at the way James Joyce presents Ulysses, is that domesticating a classic? Think of it as an experiment in relation to a well-known text in another language.

If language naturally evolves to serve the needs of tiny rodents with tiny rodent brains, then what's unique about language isn't the brilliant humans who invented it to communicate high-level abstract thoughts. What's unique about language is that the creatures who develop it are highly vulnerable to being eaten.

There is an old Italian proverb about the nature of translation: "Traddutore, traditore!" This means simply, "Translators-traitors!" Of course, as you can see, something is lost in the translation of this pithy expression: there is great similarity in both the spelling and the pronunciation of the original saying, but these get diluted once they are put in English dress. Even the translation of this proverb illustrates its truth!